A research for Our craft is our heritage

June 12, 2023 . 8 min.

Basket weaving is one of the most widespread crafts in the history of human civilisation. However, it is difficult to determine exactly how old it is because the natural materials used, such as wood and grass, rot quickly. As a result, much of the history of basketry is not scientifically documented. What is well known is that baskets have always been valued as functional and durable objects of daily use. Good craftsmanship is everlasting.

The basket from Romania was bought 40 years ago in Mediaș and taken to Germany, where it is still used every day.

on arrival at Ellis Island, New York (US), c. 1906

The craft of basketry was considered very prestigious, especially within the Roma community. This ethnic group, consisting of many subgroups, is the largest ethnic minority in Europe. The Indo-Aryan Romanes is their common language and the Indian subcontinent is presumed to be their historical-geographical area of origin.

One of the handicraft skills the Roma brought with them from India is basket weaving. It is one of the oldest and most appreciated Roma professions. The community led a non-sessile lifestyle, often enforced by discrimination. The profession of basket weaving facilitated relocation, as willow, their preferred material, was available everywhere in nature, at no cost. Most Roma families travelled and lived in a caravan, from which they also offered their basketry.

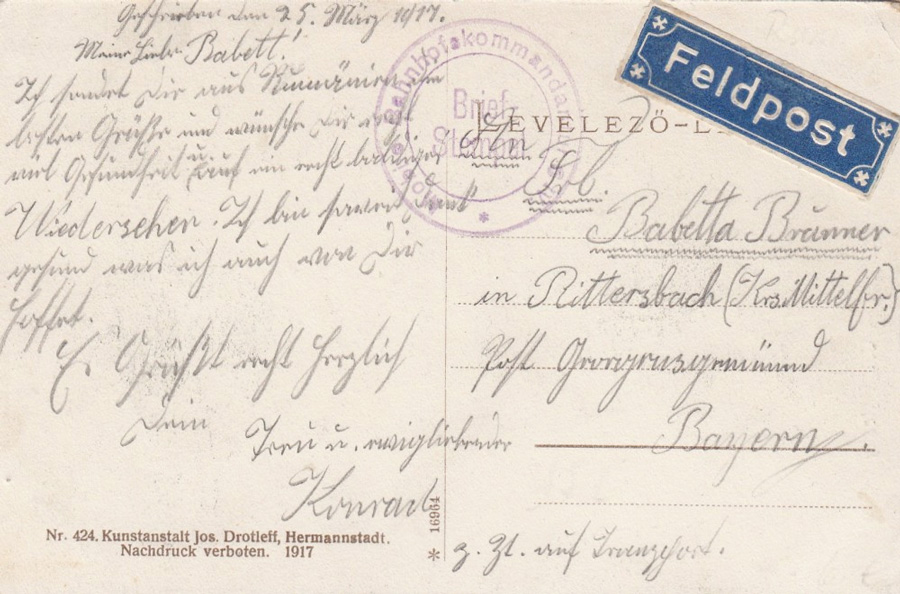

Romania, 1917

The motif appears on a postcard

Konrad sent from Romania to Babetta in Germany

during the First World War.

Europe, c. 1900

Europe, 1930s

In Eastern Europe, basketry was of particular importance in the Greek-Turkish region, in the community of the Sepečides (basket weavers). Until the middle of the 19th century, entire Roma settlements were able to earn their living with basket weaving. Their craftsmanship was respected and admired.

All social classes depended on the services of the Roma, as there was no alternative to woven baskets. They were used in agriculture, for storing and carrying food. Because of their light weight and high stability, baskets were also good for transporting wood, metal or stones.

Constantinople, today Istanbul (TR), c. 1890

The traditional Roma basket models include the ‘corfa’ and the ‘coş’. The ‘corfa’ has the shape of a hemisphere and two handles, which allows it to be carried by two people. The ‘coş’ has a cylinder shape and a straight bottom, which makes it stable to stand on. Thanks to the wicker the baskets are also robust and durable.

The Roma living in Romania were also skilled basket weavers. The so-called ‘coșari’ (basket weavers) needed manual skills and knowledge about harvesting and processing raw materials, something that was passed down through generations, especially within the family.

Bucharest (RO), c. 1900-1919

Collection of the Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen (NL)

Merica Râmniceanu (RO), 1940/1941

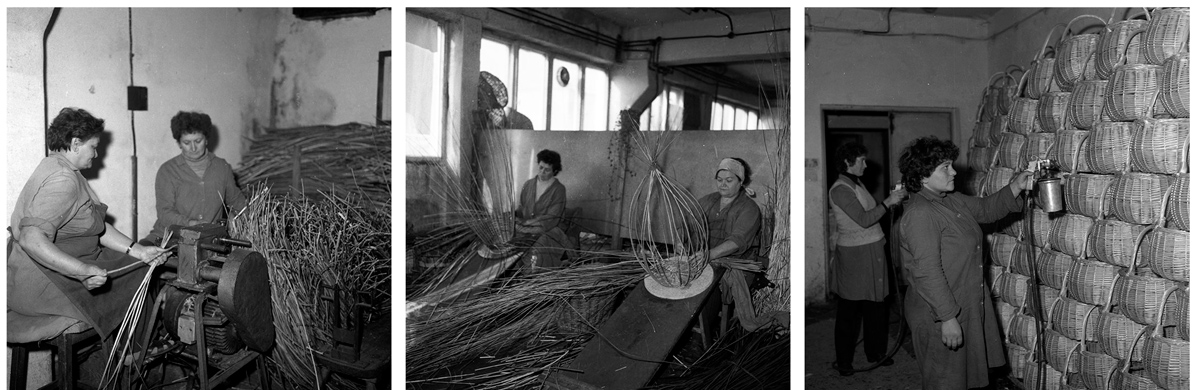

Basket factory in Gherla (RO), 1987

Weaving baskets for generations

At the beginning of the 19th century, baskets are also constantly needed utensils in Transylvania, in the south-eastern Carpathian region. They are mainly sold by itinerant craftsmen and traders. Professional basket weavers who run a workplace with a retail shop are rare.

Andreas Müllner, an immigrant from Vienna, sees this as an opportunity and opens a basketry business in 1867 in Brașov on Rossmarkt (today Breiter Bach, house no. 46).

He stands at the beginning of a chain of basket weavers that stretches to the present day. So the knowledge of basket weaving has been passed down through many generations.

–Andreas Müllner (1828-1906)

–Andreas Kravatzky (1866-1931)

–Alexander Franz Kravatzky (1907-1982)

–Gerhard Mix (1920-2017)

–Günter Mix (1956)

–Alice Dicks, née Mix (1965)

–Esmé Hofman (1971)

Andreas Müllner (1828-1906)

Andreas Müllner brings his knowledge of basketry from Vienna. He arrives in Transylvania (then Kingdom of Austria-Hungary, today Romania) in 1848, together with his friend Johann Krawatzky. In the name of the Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph, they fight against the Hungarians who settle here and want to force their independence. Andreas and Johann remain in Transylvania even after their discharge from the military and marry women from Hărman. At home, they maintain many Austrian customs and speak German.

Years later, Johann Krawatzky sends his son Andreas to apprentice with his friend Müllner. Andreas learns the craft of wickerwork in Brașov and soon marries the daughter of the house, so that the two families become closely related.

Andreas Kravatzky (1866-1931)

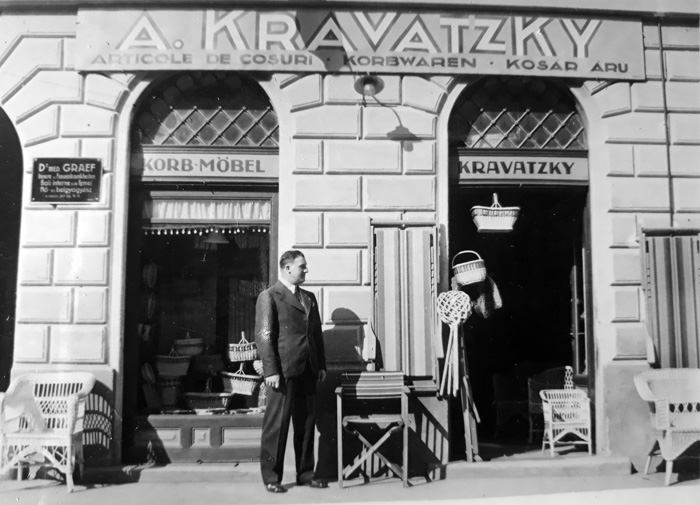

After years of apprenticeship in Brașov and Vienna, Andreas Krawatzky moves in 1889 to Bucharest, the capital of neighbouring Romania, where he opens his own basketry. The economy is booming and wickerwork of all kinds is in demand. Andreas soon becomes a royal purveyor. During this time he also changes the spelling of his name to Kravatzky. After ten years in Bucharest, the family returned to Brașov, where Andreas took over the basket weaving business of his father-in-law Andreas Müllner.

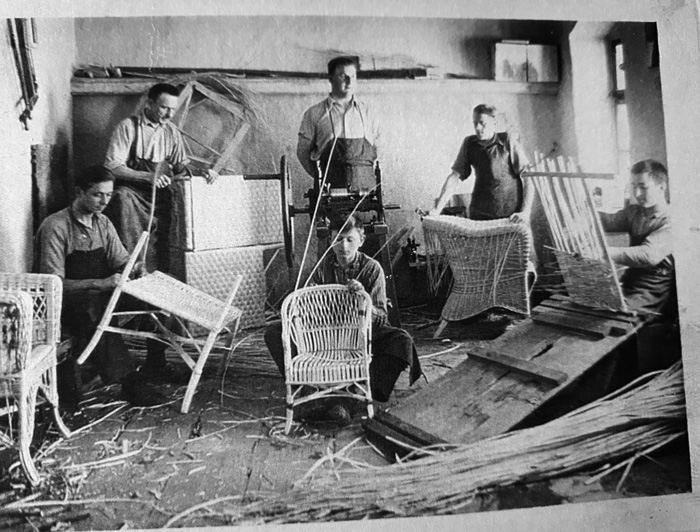

and apprentices in his workshop, Brașov (RO), 1926

on Hirschergasse, Brașov (RO), 1931

Alexander Franz Kravatzky (1907-1982)

The youngest son Alexander follows in the footsteps of his father Andreas. He completes his apprenticeship as a basket maker and continues to run the business after his father’s death in 1931. Over the years, he expands the company, hires employees and supervises the training of apprentices. One of them is Gerhard Mix, who comes from a German family from Bessarabia (today Ukraine).

far right the apprentice Gerhard Mix, Brașov (RO), 1936

The political turmoil of the Second World War has lifelong consequences for both Alexander and Gerhard. After returning from forced labour in Russia and later on the Danube-Black Sea Canal, Alexander Kravatzky finds his family dispossessed. He fights for the return of the workshop in Brasov and is able to keep his head above water with custom-made products despite the declining demand for basketry.

The passing on of his craft within the family also seems assured. His eldest son Dieter-Jochen begins an apprenticeship as a basket weaver. However, when new legislation passed by the communist rulers in 1956 forbids private craftsmen from employing apprentices, the boy is forced to leave his father’s business. In the 1970s and 1980s, Alexander’s children emigrate to Germany. He himself prefers to stay in Transylvania for life.

Gerhard Mix (1920-2017)

During the Second World War, the apprentice Gerhard Mix also arrives in Germany. He brings the basketry skills he learned in Brașov with him and opens his own business in Freiberg am Neckar in 1946. Three of his children also learn the craft of basket weaving. His daughter Alice is apprenticed to her father. His sons Uwe and Günter are trained at the School for Basketry Design in Lichtenfels (DE).

at the market in Kirchheim am Neckar (DE), 1960

in Freiberg am Neckar (DE), c. 1995

in Freiberg am Neckar (DE) from 2011 to 2018

Basketry Design, Lichtenfels (DE), 2022

Günter Mix (1956)

Alice Dicks, geb. Mix (1965)

Gerhard Mix’s basket weaving business existed for 72 years. The shop has been run for the last seven years by his daughter Alice, who closes it in 2018, one year after her father’s death.

Gerhard Mix’s main focus in life was his craft. He could still be found in the workshop every day until shortly before his death at the age of 97.

Günter Mix, who found the inspiration for basket weaving in his father’s workshop, passes on his craftsmanship as a specialist lecturer. Until his retirement in 2022, he teached at the School for Basketry Design, Lichtenfels, the only school of its kind in Germany. So it could well be that parts of the artisanal knowledge from Brașov have been passed on to students in Germany more than 150 years later, who in turn carry it into the wider world.

It is mainly women who are interested in training as basketry designers. Many graduates practise the profession part-time and work alone. They make one-off pieces, give workshops and develop exceptional custom-made products.

of the School for Basketry Design, Lichtenfels (DE), 2020

Esmé Hofman (1971)

Esmé Hofman, a basket weaver from the Netherlands also studied in Lichtenfels (DE), among others with Günter Mix. She produces selected basketware on commission and also works as a curator, lecturer and consultant. In the Netherlands, she is the only one who professionally practices the labour-intensive willow skeinwork with shavings from split willow branches. She learned this technique, which is threatened with extinction, during her education in Germany and uses it in restoration work for museums and private clients.

Hofman also finds it important to search for new, creative applications for her craft in interdisciplinary and experimental projects with artists and designers. In order to keep it alive and to pass on the techniques to following generations, she gives training courses and readings.

Cone 1 and 2

willow skeinwork by Esmé Hofman (NL), 2013/2015

Collection Harmen Brethouwer/Museum Boijmans van Beuningen (NL)

willow skeinwork by Esmé Hofman (NL), 2017

basketry technique of hand coiling, plastic, 3D printing

by Amandine David, Ésme Hofman and Joris van Tubergen (BE/NL), 2021

Setting up a basket weaving workplace with a retail shop is no longer profitable. In the last few decades, peddigree cane and rattan have come into fashion as weaving materials, and since these grow mainly in Indonesia and China, the triumph of Asian basket makers was inevitable. In addition, craftsmen in Eastern Europe also offer their goods at a lower price than Western European producers.

Even within the Roma community in Eastern Europe, the importance of basketry as a craft has steadily declined over the last century. They faced significant competition from factories, where wickerwork was mass-produced, automated and reproduced according to external designs.

Roma families have only been able to preserve the old tradition of basket weaving in a few villages in the Eastern Carpathians of Ukraine, for example in Iza near Khust, a village that has been known as a centre of basketry since the 19th century.

Over time, the craft became the main occupation of all inhabitants. Today, the streets of Iza look like an open-air museum. Most of the locals display their goods along the street and along their fences and sell them mainly to tourists.

in Iza (UA), 2022

In Romania, there are only a few professional basket weaving workshops left. Toderașcu Artizan in Sat Heci, near Iași, is the only professional business in the north-east of the country producing hand made high-quality wickerwork. The craft has been passed down in the Toderașcu family for three generations.

Lilian Toderașcu learned the handicraft from his father and founded the basketry business, where his son Tudor Alexandru Toderașcu now also works. Their own willow plantation helps them guarantee the quality of the wickerwork, which they increasingly promote and sell on the Internet. The huge range consists of utilitarian items such as furniture, baskets, bags, toys and unusual accessories.

Sat Heci (RO), 2022

Crafts as an artistic experiment

Basketry has become a niche craft practised by only a small group of artisans and artists. It is perceived as the result of a creative process and as a cultural product. Objects from the Kravatzky and Mix basketry workshops are now museum objects as well. They have been included in the collection of the Transylvanian Museum (Siebenbürgisches Museum) in Gundelsheim/Neckar (DE) and bear witness to the fact that basketry once flourished as a commodity.

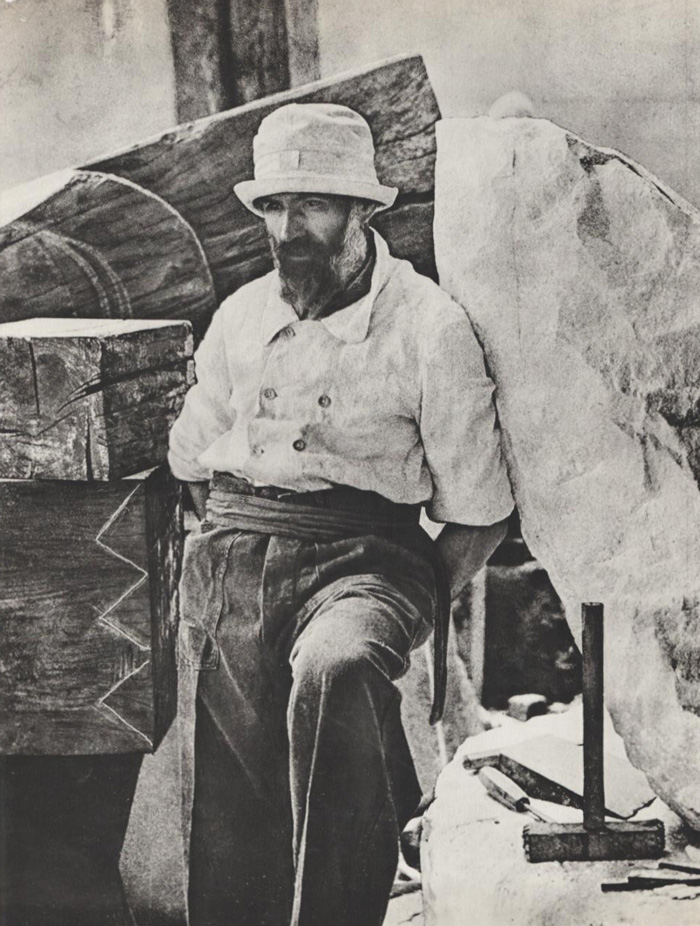

For artists, traditional crafts have long held a special attraction. They are a symbol of authentic work and of nature. The sculptor Constantin Brâncuși (Hobița, 1876-Paris, 1957) is considered a great role model. His signature style was influenced by Romanian folk art.

by Constantin Brâncuși, Paris (FR), 1920-1922

Brâncuși was born at the end of the 19th century in a small Carpathian village in Romania with a population of no more than a few hundred. He studied in Craiova and Bucharest before going abroad in 1903. By then, the traditional crafts of the villagers had already left a lasting impression on him.

Years later, Brâncuși introduces the technique of ‘direct carving’, by sculpting stone or wood directly and without an artistic model. He also builds various furniture, household utensils and tools – a distaff, a stove, lamps and plumb bobs. Together with his sculptural art, these utilitarian objects merge into a unity in his Paris workshop. Until his death, he transforms his studio, located at 11 Impasse Ronsin, into a Gesamtkunstwerk.

Reconstruction of Atelier Brâncuși

by Renzo Piano Building Workshop (FR), 1992-1996

The merging of handicraft and art forms an important inspiration for many contemporary artists. In addition, in times of climate crisis and slow living, there is a resurgence of handicraft with natural materials. Artists cite crafts or experiment with handicraft techniques and materials. In doing so, they find it important to respect nature and to produce sustainably – to use only as much plant material as can grow back.

made of macramé, rattan and wood

by Maddy Arkesteyn (BE), 2010-2012

from willow bark, pine roots and freshwater rushes

by Rachel Frost, traditional hat maker (UK), 2022

Adrianus Kundert and Crafts Council Nederland

Exhibition at Dutch Design Week (NL), 2021

In the Netherlands, the Crafts Council Netherlands is the most important initiator, inspirer and facilitator for all crafts. They promote the revaluation of creative crafts and the preservation of craft techniques. The fact that experimentation is very important in the Netherlands is clearly reflected in their initiatives.

In their annual programme Bask It! (2021), the CCN explored new applications, as well as the social context of three-dimensional weaving, in interdisciplinary projects, exhibitions and workshops. Dutch designer Adrianus Kundert curated an exhibition on basketry for the occasion. He himself explores the design possibilities of weaving in his practice and in the Basket Club he co-founded. In his design projects, he integrates the art of basketry, which demands a slow, time-consuming effort, into new contexts and production processes.

by Adrianus Kundert (NL), 2021

by Rachel Evans (UK), 2021

The 90 baskets were produced by the Gyana basket weaving company in Cernica.

Romanian artist Maia Ștefana Oprea came to basket weaving through material explorations of paper, plastic and textile strips. She has developed a fascination for the reuse of waste products – the colour, texture and durability of plastic, plastified cardboard and tinplate.

In the garden of her house in the countryside near Inotești (RO), she stores up to a hundred kilogrammes of plastic waste that she has collected over the last ten years. The artist Samir Mihail Văncică built a recycling depot for her collection.

made from recycled plastics

by Maia Ștefana Oprea (RO), 2022

“The most important aspect of my artistic process is that I can ‘digest’ all the artificial materials that accumulate in our household, as if my art is a machine to transform the ugly into beautiful things.”

Maia Ștefana Oprea

objects made of vines, textiles, plastic from diapers packaging

by Maia Ștefana Oprea

Creart Gallery, Bucharest (RO), 2023

Maia Ștefana Oprea’s art is nourished by an experimental dynamic between a huge permaculture garden, the recycling depot, her art studio and the private household where she homeschools her three children – a continual giving and taking of inspiration and new ideas for art and a more sustainable lifestyle.

Oprea is also trying to implement this approach in the Gradina Ideilor (Garden of Ideas) in Nucșoara (RO). It is planned as an artistic community project that offers a platform for creative people at the intersection of art, sustainability and permaculture. The residence in the middle of a large garden in the Făgăraș mountains offers space, in the truest sense of the word, to reflect on art paradigms with a more sustainable future in mind. Ideally, new ideas and methods of how to produce and communicate art ‘sustainably’ will be developed here.

Harvesting plants for weaving

Maia Ștefana Oprea (RO), 2022

Meanwhile, basket weavers who do commissioned work are also experimenting with sustainable materials. Mariana Buruiană, a basketry designer from Chișinău (MD) works with paper, which is specially processed and can be tinted in a wide range of colours at the customer’s request. This not only creates new design possibilities, her products are also resource-saving and environmentally friendly.

Mariana Buruiană (MD), 2022

I asked Mariana Buruiană about her approach.

Here you can read my interview with her.

The craft of basketry, as I discovered during my research, is practised less, but all the more inventively. It is currently being revived by artists and extremely creative craftsmen. An extinction of the craft is not yet in sight.

Sources: rombase.uni-graz.at; flechtausbildung.de; notes by Manfred Kravatzky; conversation and exchange with Günter Mix, Maia Ștefana Oprea, Esmé Hofman

This research is made possible with the support of DutchCulture (NL)

Follow my visual research on Instagram.

Share: