Visual article by Gerlinde Schuller

4 October 2022 . 7 min.

Bucharest became the capital of the Principality of Wallachia in 1659 and later of Romania. The city is the political, economic and cultural centre of the country and has always been the scene of turbulent political shifts.

In the four decades following the Second World War, the capital grew to more than double its population and underwent critical transformations under communist dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu. Today, the city is both a contemporary metropolis and a public museum of cultural heritage.

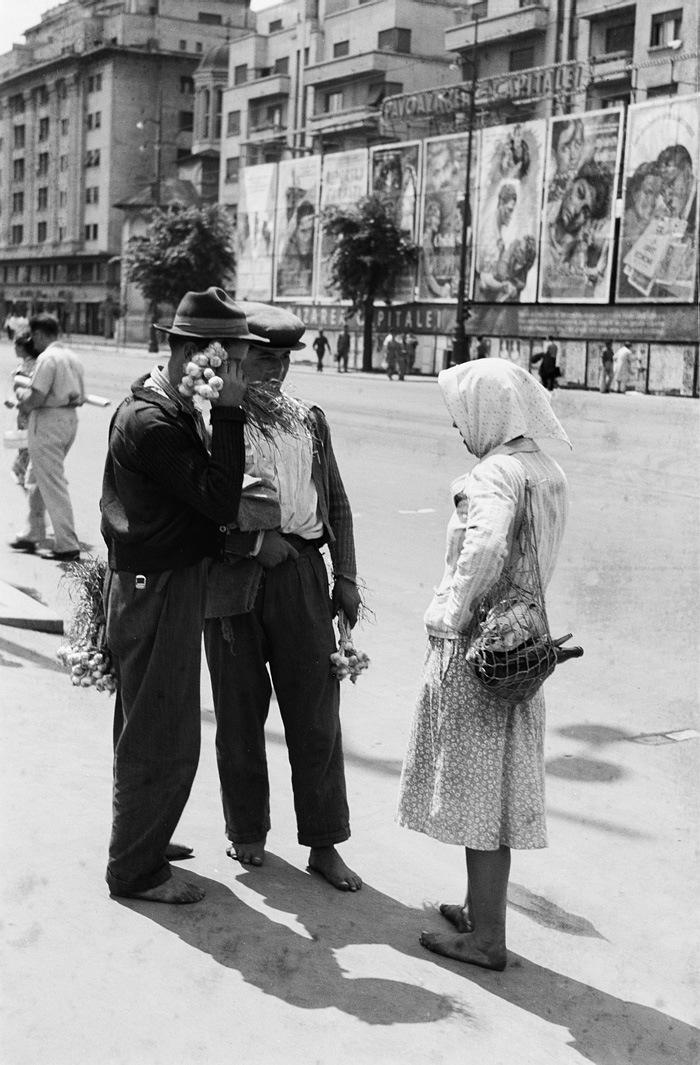

1956

In the mid-1950s, photojournalists from the German Democratic Republic (GDR), visit the Romanian capital Bucharest to document public life.

They find a modern, culturally enthusiastic city, accessible to both the wealthy bourgeoisie and the working class. Romania has been a People’s Republic since 1948 and is on its way to becoming a country where prosperity is a right for all.

Head of state Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej initiates the Sovietisation of Romania and the establishment of the security service Securitate. Industry and agriculture are being nationalised.

Bucharest has 1.2 million inhabitants and is growing rapidly. Peasants increasingly come to the city to find jobs in the large industrial enterprises. They bring their rural way of life with them, which contributes in shaping the new image of Bucharest.

Bucharest based photographer Octavian Pavel helped to identify

the locations on the following archive images.

Boulevard Regina Elisabeta

(Cercul Militar Național)

1950s.

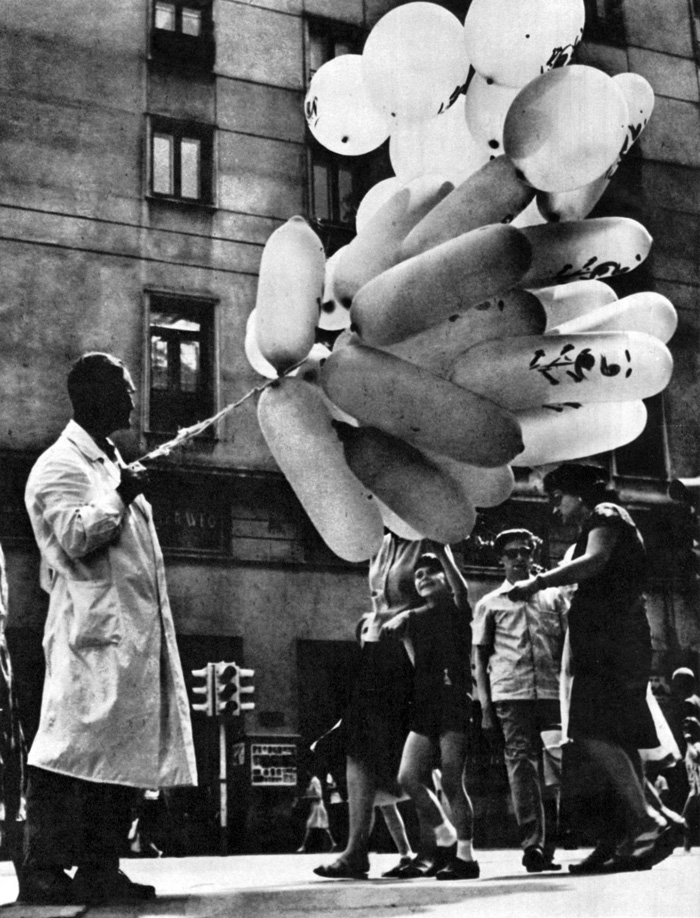

1959

in the background, 1959.

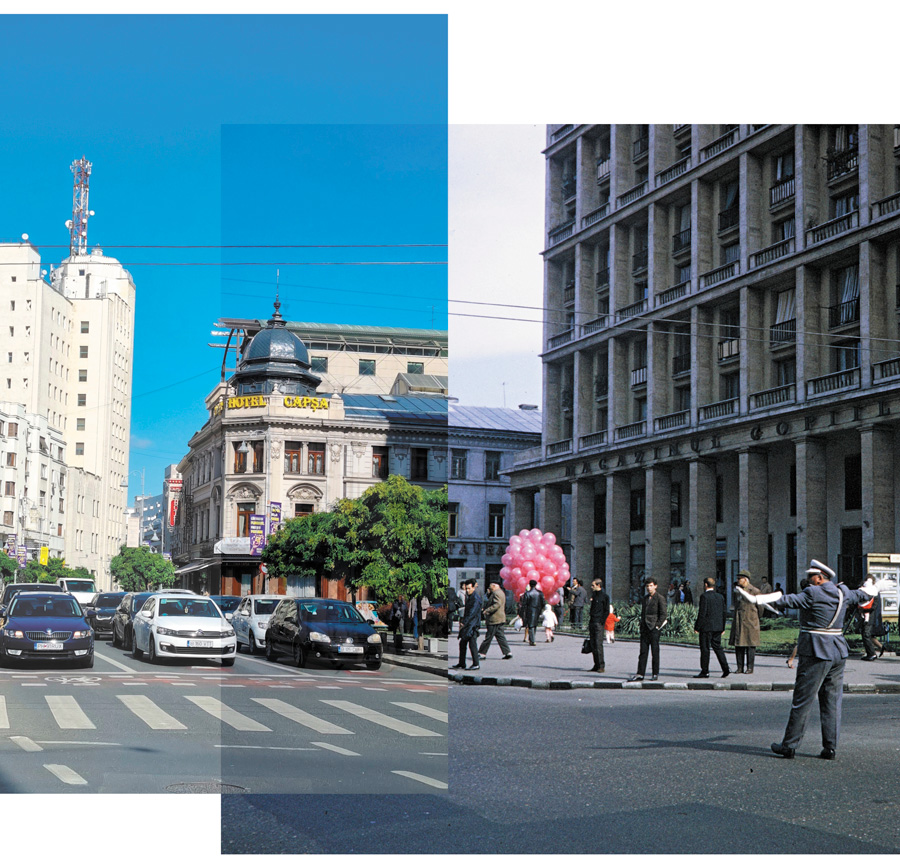

2020 I 1970

and the telephone company building, 2022/1970.

In the early 1970s, Bucharest is the centre of political power for communist leader Nicolae Ceaușescu. The toy shop is still in the same place. The city, on the other hand, has turbulent years behind it and ahead of it. The frequent change of names of ‘Regina Elisabeta Boulevard’ bears witness to this.

In 1870, it was opened to traffic as ‘Boulevard Doamna Elisabeta’. Until 1930 it is called ‘Boulevard Academiei’, then it is renamed ‘Queen Elisabeta Boulevard’, after the first queen of Romania.

In the first year of the Romanian People’s Republic in 1948, when the names associated with the old regime are exchanged, the street is called ‘Boulevard 6 March’ (Feast Day of Orthodox Christians).

After only 17 years, in 1965, after the death of the communist leader Gheorghiu-Dej, it is given his name: ‘Gheorghe Gheorgiu-Dej Boulevard’.

1970

In 1990, after the Romanian Revolution, the street is first named ‘Mihail Kogălniceanu Boulevard’ after the liberal statesman, only to be renamed ‘Elisabeta Boulevard’ in 1995. Two months later, it finally gets the name ‘Regina Elisabeta Boulevard’, which it still bears today.

In 2022, the perspective in the historic photo does not seem to have changed significantly.

2022

Monica Mărăcineanu documented the intersection in September 2022. She lives in Bucharest and has photographed more than 4000 houses in the last five years. Mărăcineanu is particularly interested in historic buildings, many in need of renovation. With her almost systematic registration of these houses with historical patina, she reminds us of the importance of preserving this cultural heritage.

The old buildings she shoots are archives of a past worth preserving for the next generation. Mărăcineanu makes us aware that without the knowledge of the past we cannot really evolve.

2006 I 1969

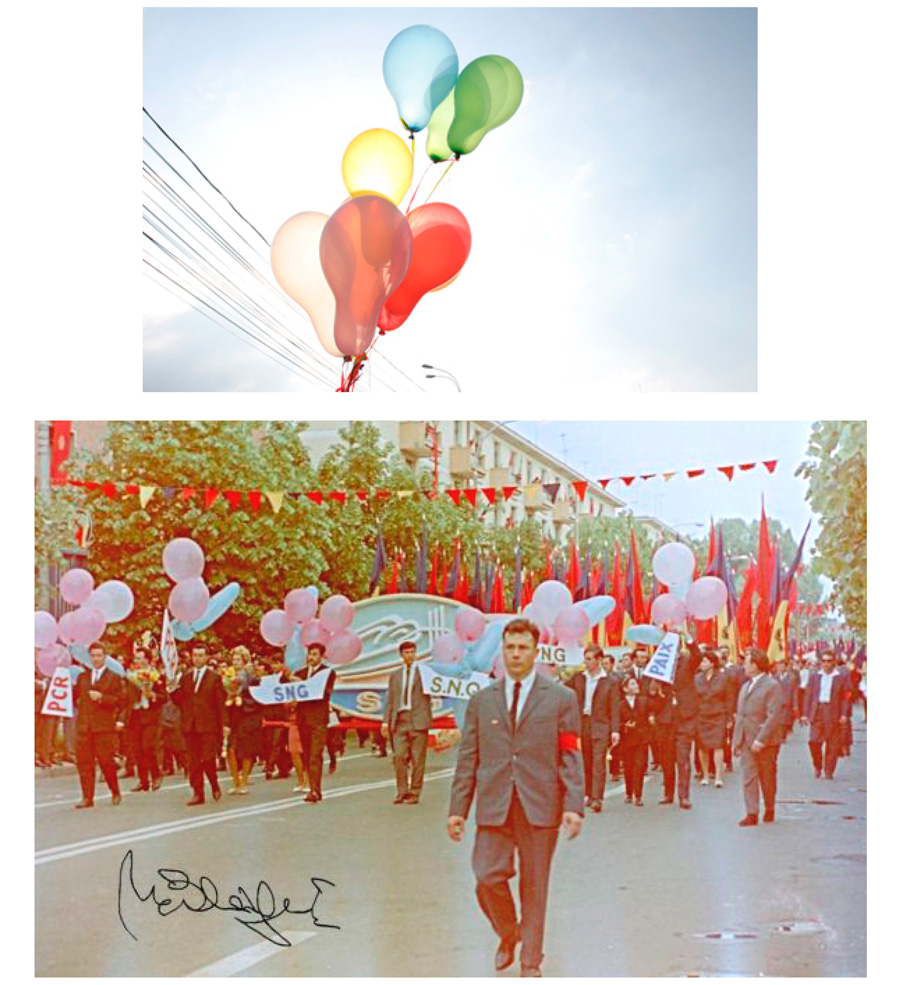

the 1 May Parade in Galați, 1969

1 May 1969

Under the communist government of Nicolae Ceaușescu, 1 May, as ‘Workers’ Day’, is celebrated with propaganda events and parades (defilare) in which thousands of people participate.

Workers are obliged to participate and are mobilised by Romanian Communist Party activists to chant praises and salute in front of stands with party comrades. The choreographies are pre-scripted and must be carefully rehearsed beforehand. It is a day on which the Communist Party and Ceaușescu present their achievements and let themselves be celebrated.

After the 1989 revolution, 1 May is still celebrated as ‘Labour Day’, but only with social and private events in the open air.

3 June 2006

The Bucharest Pride Festival has been held annually since 2004 and is dedicated to LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender) rights in Romania.

Only three years earlier, the law punishing public manifestations of homosexuality was repealed in Romania. Same-sex marriage is still not legally recognised until today.

In 2022, up to 15,000 people take part in the Pride Parade and campaign for more rights for sexual minorities. They fear backward steps in legislation, as the Hungarian Minority Party (Magyar Polgári Párt) is currently trying to push through an anti-LGBT law like in neighbouring Hungary.

1980s

Nicolae Ceaușescu during the 1 May parade, 1980s

2022

2008 I 1990

the Palace of Parliament, Bucharest, 2008

Romanian soldiers in front of the same building,

a few months after the revolution, 1990

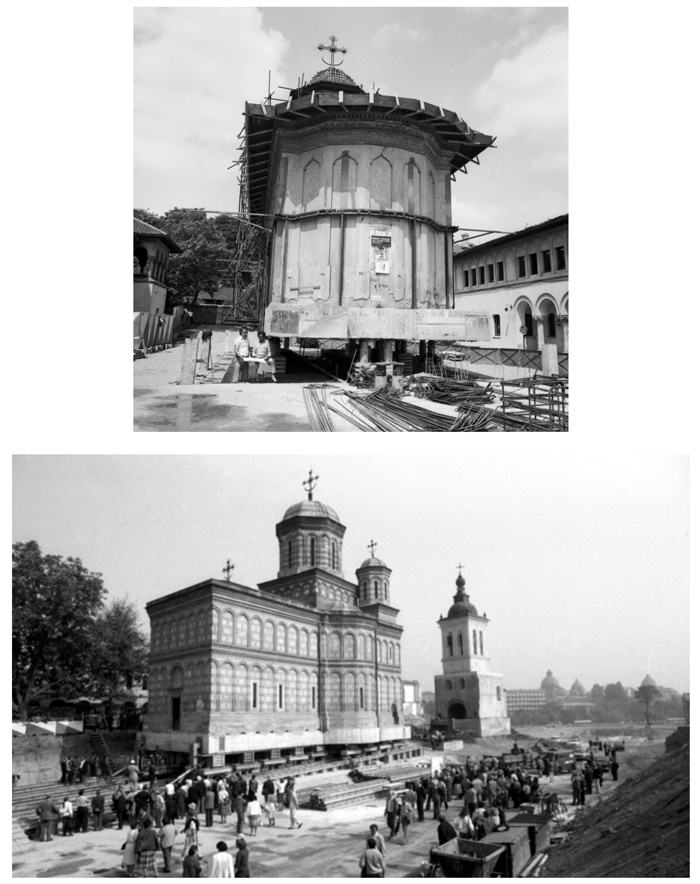

The Palace of Parliament (formerly ‘House of the People’) is the seat of the Romanian Chamber of Deputies and the second largest building in the world. It is built between 1983 and 1989 according to the ideas of Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu – a work effort undertaken by 20,000 workers, mostly military personnel, in three shifts.

A severe earthquake in March 1977 provides Ceaușescu with the pretext to initiate a reconstruction plan for Bucharest in the style of socialist realism. The Palace of of Parliament is the centrepiece of this project.

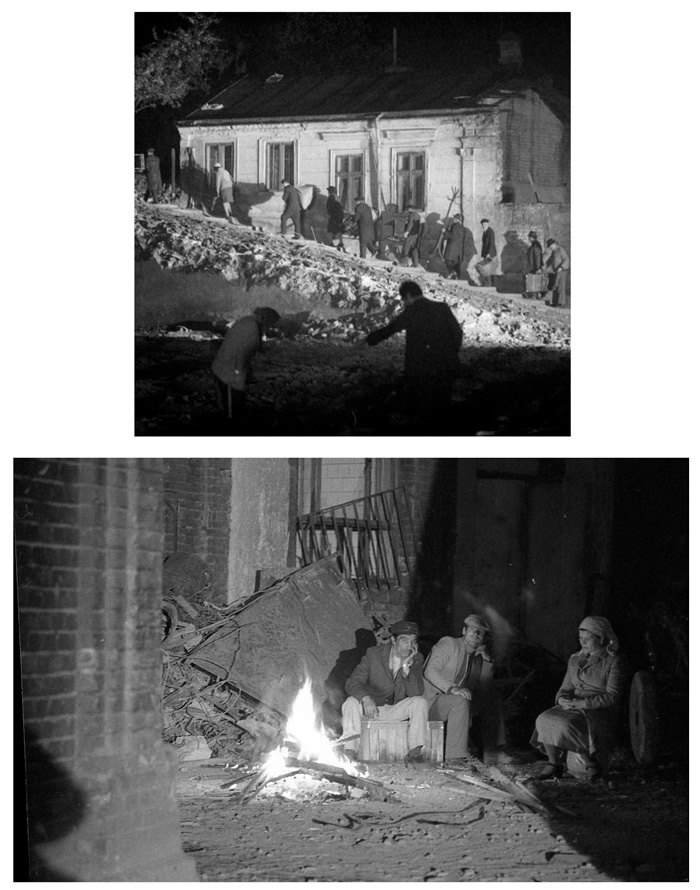

To make room for this superlative building and its infrastructure, a large part of Bucharest’s old town is being demolished, including 19 Orthodox Christian churches, six Jewish synagogues, three Protestant churches and around 30,000 flats. Also affected is the historically important Uranus district from which people are being forcibly evacuated. After international protests, several churches that have been ordered to be demolished are elaborately relocated. An urban texture that has grown over centuries is destroyed, leading to severe trauma in many of those affected, from depression to suicide.

Today, the Palace of Parliament is both a reminder of the communist era and a symbol of power in Romania. The distribution of power takes into account the 17 ethnic minorities in the country. Parties representing national minorities have the right to one seat in parliament, regardless of the number of votes they receive.

The spacious square in front of the building has been used for demonstrations of all kinds since the Romanian revolution.

1980s

and the Mihai Vodă Monastery, 1985

ca. 1984

the Palace of Parliament, 1980s

1990

of the Palace of Parliament, 1990

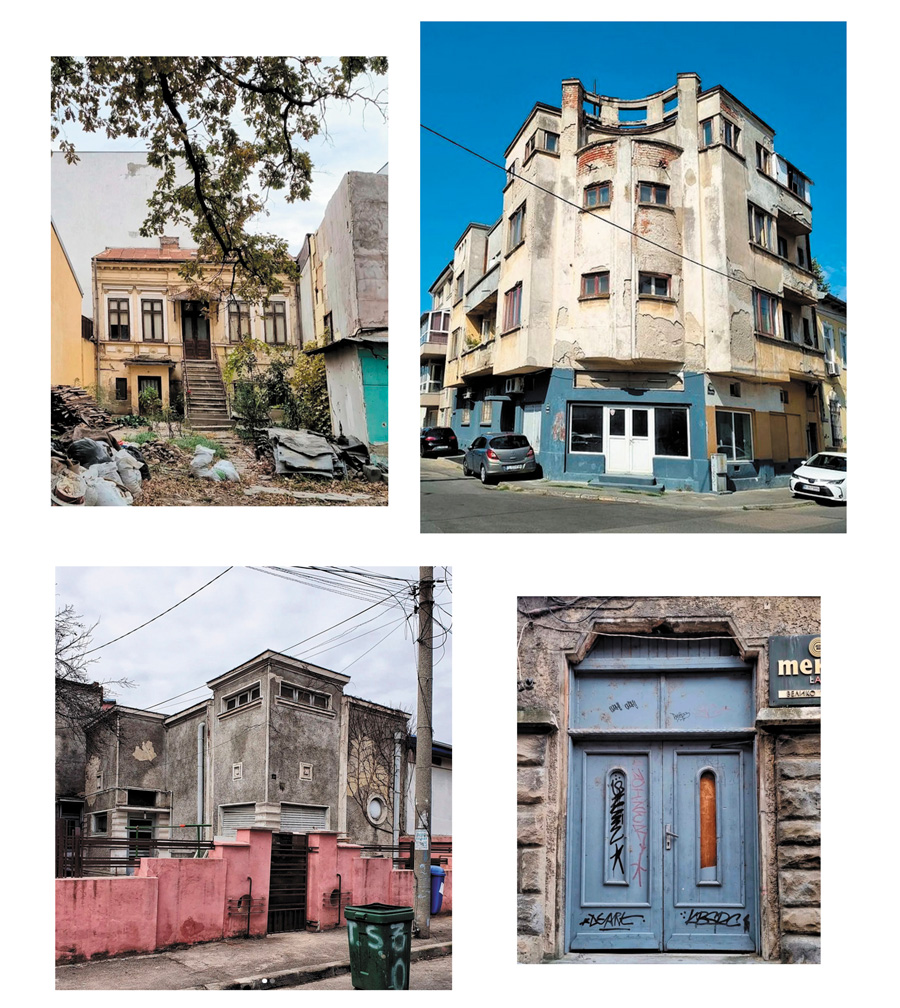

2022

In the last decade, Bucharest has become a popular tourist destination. Many monumental buildings have been renovated, the tourist sights are especially spruced up. The city presents itself as cosmopolitan. At the same time, it has a rough and peculiar facet that not everyone gets to see or wants to see. The one who registers these characteristics of Bucharest like no other is Dragoș Alexandru.

I see something you don’t see

Photo documentation of coincidental moments in Bucharest, Romania by Dragoș Alexandru

2015-2022

Dragoș Alexandru’s shots of the city seem timeless. For instance, he photographs the Palace of Parliament (formerly House of the People), usually depicted as a splendid building, in the mist. Mysteriously, it thrones out from behind taxis, tourist buses and a row of mobile toilet cabins, without making a spectacular impression.

The Palace of Parliament embodies the communist dictatorship of Nicolae Ceaușescu and the current democracy in Romania. Alexandru’s photo also merges layers of time. It is not immediately chronologically classifiable and that is what makes it so appealing. It may be that Alexandru succeeds in capturing this timelessness so well because he himself experienced the most important historical shift in Romania. He grew up in communist Romania, witnessed the 1989 revolution and the transition that followed.

Alexandru has lived in Bucharest for 20 years now and enjoys documenting situations that happen quietly, in passing. He plays with us the children’s favourite guessing game ‘I see something you don’t see’, and captures circumstances that most of us would not pay attention to. Often, photos of coincidental moments emerge. There is a lonely rooster running across the street, a man has dozed off on his accordion, a painted portrait of a woman has been left outside the front gate and a cluster of nine balloons has been forgotten on a tree. At first glance, these seem to be motifs that could be found in any big city. But if you look closely, you realise: this can only be Bucharest!

Alexandru has perfected his X-ray vision of the city and shows us its strange, disturbing side in visually appealing snapshots. They are often situations that have evaporated in the next moment. While we would still be wondering: Where does the rooster go? Isn’t the man lying uncomfortably? Who might the woman in the painting be? Why don’t the balloons fly away? Alexandru has already taken a photo and is seeking a new moment of surprise.

I asked Dragoș Alexandru about his approach to documenting Bucharest. You can read my interview with him here.

Follow my visual research on Instagram.

Share: