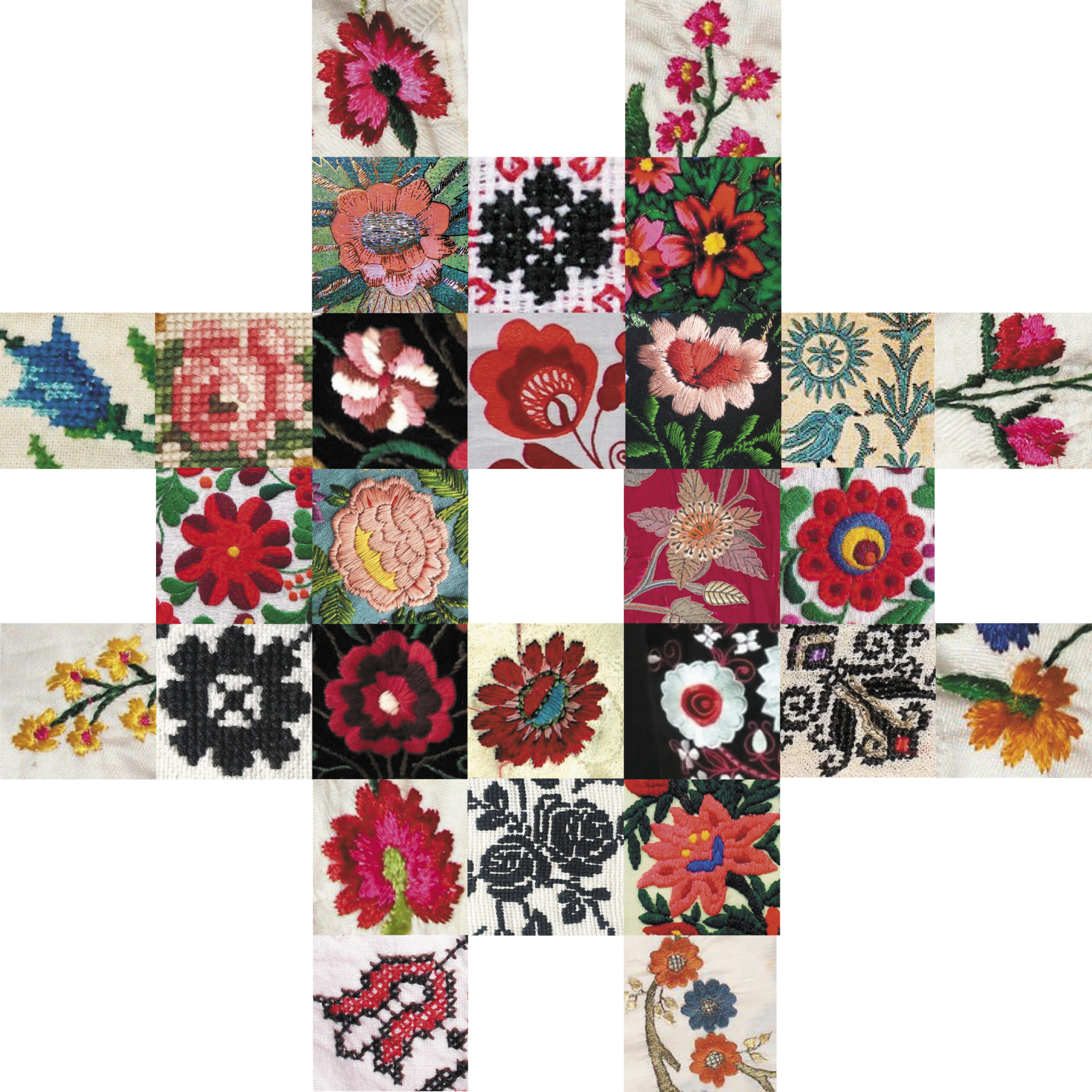

My inspiration sources

Gerlinde Schuller

June 7, 2023 . 8 min.

Romania’s cultural heritage is characterised by a colourful, unique diversity. This was brought about by the coexistence of Romanians with up to 18 ethnic minorities.

and various ethic communities, Romania, ca. 1880-2023

These colourful images prove that Romania developed into a multi-ethnic state centuries ago. After Russia, it is the European country with the most minorities. The most common minorities in Romania are Hungarians, Roma, Germans, Armenians, Italians, Bulgarians, Greeks, Jewish communities, Lipovan Russians, Croats, Albanians, Tatars, Ukrainians, Slavic Macedonians, Serbs, Ruthenians, Turks, Slovaks and Czechs and Poles.

Today, 18 ethnic groups are officially recognised as minorities and each has its own representative in parliament. Various laws also ensure that all minorities can preserve their own language, culture and religion. Romania reflects Europe in miniature.

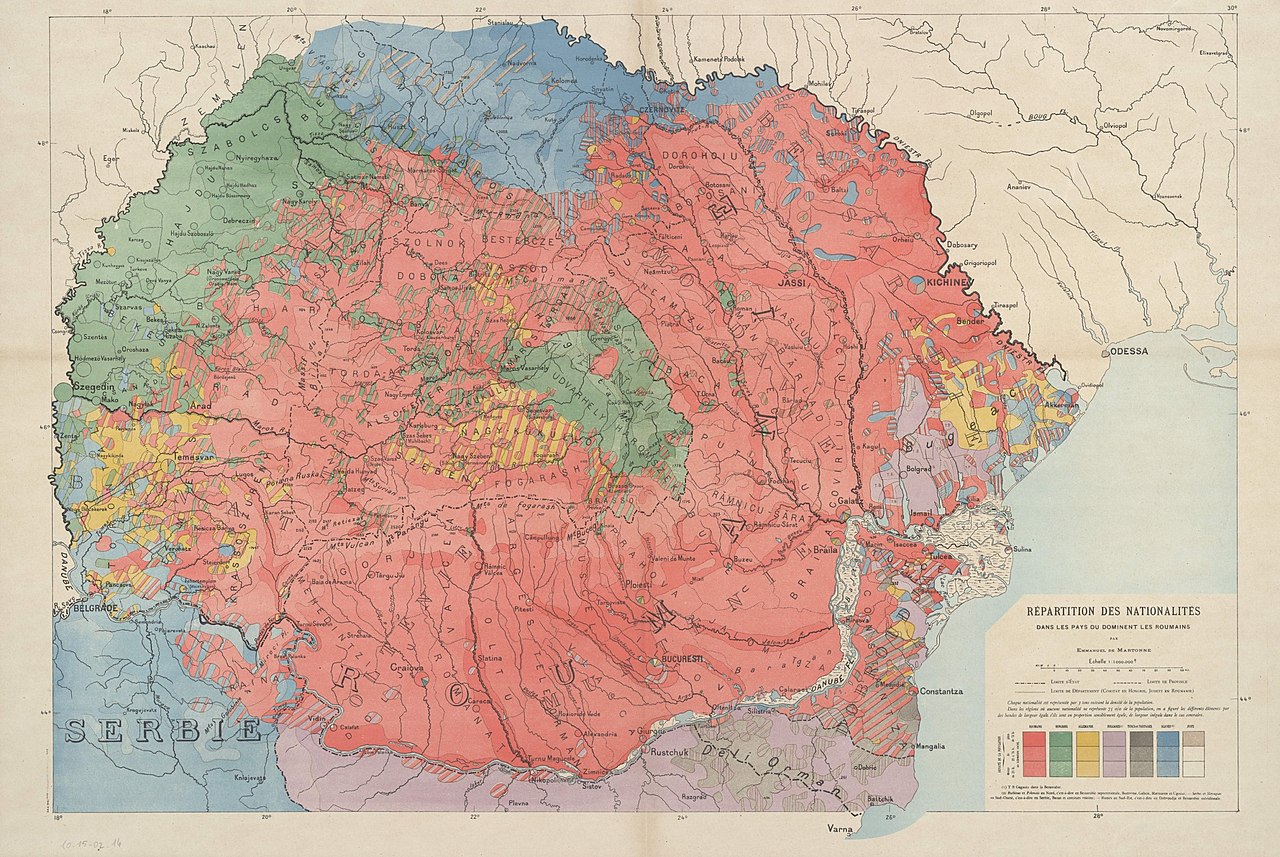

documented by the French geographer Emmanuel de Martonne.

His map played an essential role in defining the borders of Romania,

most of which still exist today.

The fact that so many ethnic groups have intermingled with the majority population over centuries is a breeding ground for the diversity of traditions and crafts. They are characterised by a multitude of regional and local expressions and extraordinary mergers.

In Romania’s history, this has not always been seen as an enrichment. Especially in times of war and communism, ethnic minorities were granted few rights. However, after the revolution, from 1990 onwards, the country has become a forerunner in the field of inter-ethnic relations and integration.

A new generation has realised that the identity of minorities complements Romania’s historical narrative. Among them, there are individuals, cultural workers and organisations who strive to protect Romania’s multi-faceted cultural heritage in their own way.

My personal sources of inspiration include museums, archives, artists from various disciplines, historians, ethnologists and entrepreneurs.

I introduce some of them in this article.

For clarity, the article is structured according to communities.

However, in reality they have lived together and influenced each other.

The Romanians

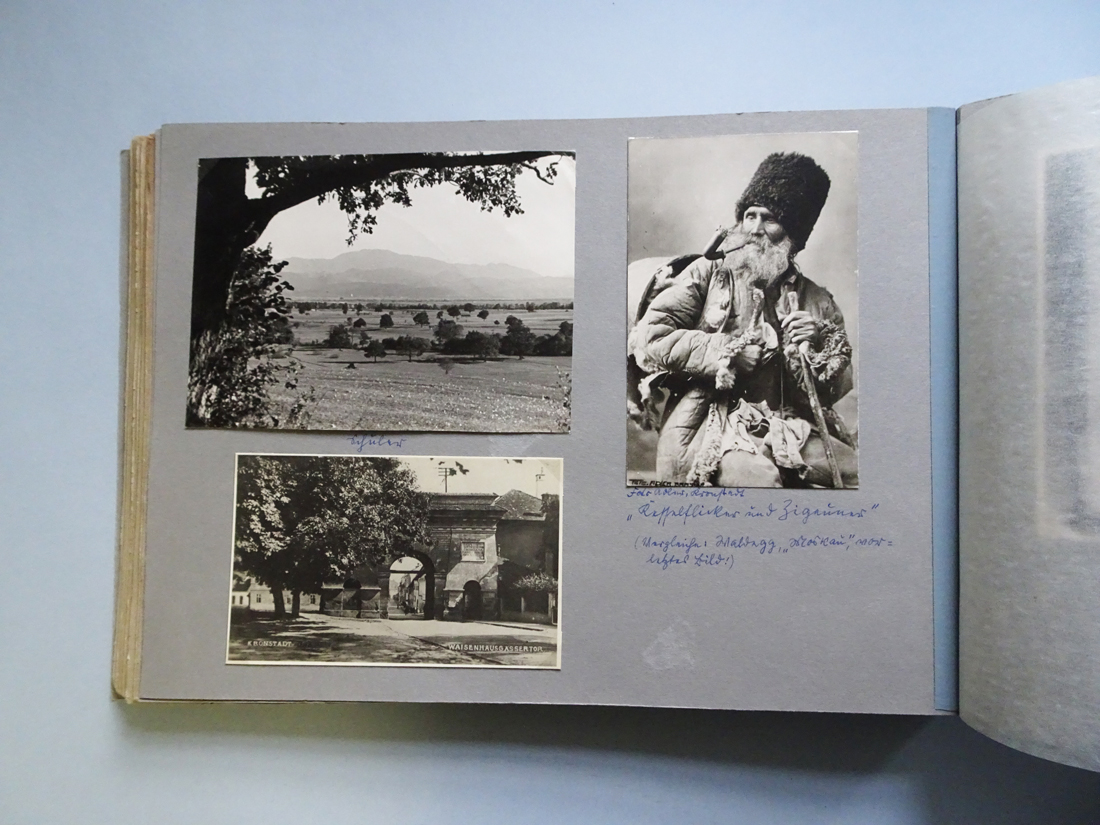

Romania (then Moldova), 1920s

The Romanians are a Romance-speaking ethnic group who share a common Romanian culture and ancestry. The last census of 2021 revealed that nearly 89,3% of Romanian citizens identify themselves as ethnic Romanians.

Both in Romanian culture and in that of the ethnic communities living in Romania, agriculture, attachment to nature and handicrafts play a significant role.

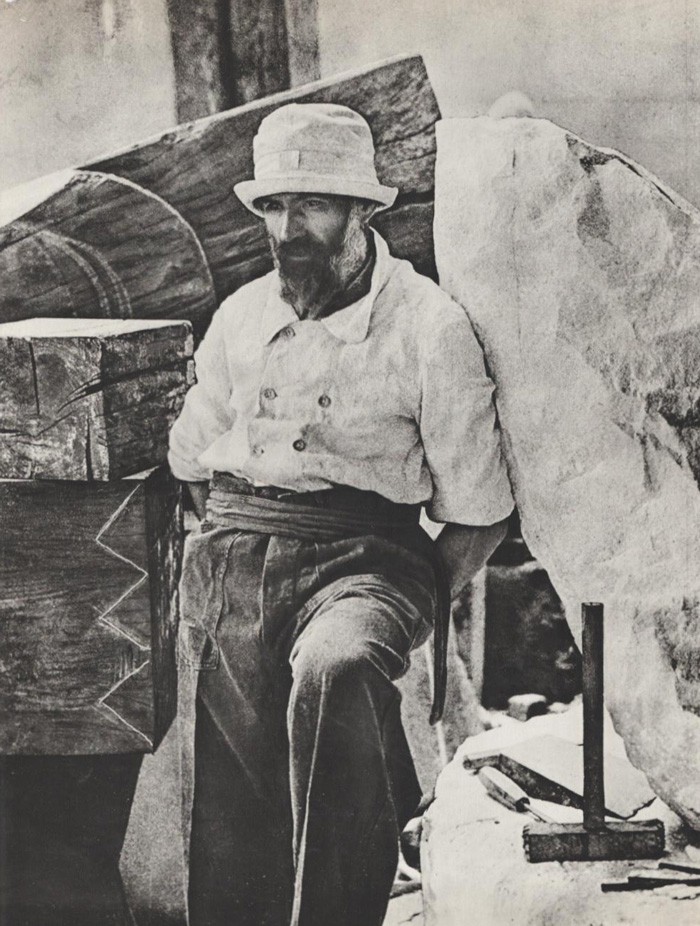

For many creative people the life of the peasants is a great source of inspiration. The sculptor Constantin Brâncuși (Hobița/RO 1876-Paris/FR 1957) is considered a great, historical role model in this respect. His style was influenced by Romanian folk art. He introduced the technique of ‘direct carving’, working stone or wood directly and without an artistic model. Furthermore, he built various furniture, domestic utensils and tools. Together with his sculptural art, these utilitarian objects merge into a unique entity in his Paris workshop. Until his death, he transformed his studio into a ‘Gesamtkunstwerk’.

A reconstruction of the Atelier Brâncuși can be seen at the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

by Constantin Brâncuși, Paris (FR), 1920-1922

Reconstruction of Atelier Brâncuși

by Renzo Piano Building Workshop (FR), 1992-1996

Romania (then Moldova), 1920s

It is to the credit of the La Blouse Roumaine community that in 2022 the art of the traditional blouse with shoulder embroidery (altiță) was inscribed on UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage List. ‘Altiță’ is an essential part of Romanian and Moldovan folk costume. It combines a simple cut with rich and colourful embellishments stitched on using complex sewing techniques. Styles and techniques vary by region and the blouse is made entirely by hand.

As the Republic of Moldova was part of Romania after the First World War and has been an independent state since 1991 only, the traditions are very similar. Stela Moldovanu from Chișinău (MD) established the MăiestrIA community in 2018. The collective offers sewing and embroidery courses where you can learn to create your own traditional Romanian blouse. In addition, Moldovanu wrote MăiestrIA – povestea cusută a iei, a comprehensive publication on the history of the Romanian blouse with many visual examples.

Romanian blouse, 2022

In the north of Romania, in the small town of Vișeu de Jos in Maramureș county, Denis Năsui strives to preserve Romanian traditions. To this end, he re-enacts scenes from peasant life, often together with Andreea Șimon. Dressed in hand-sewn rural costumes, he enthusiastically educates people about customs and folklore from the region. To turn his passion into a profession, he is now studying ethnology.

Octavia and Lucian Loiș are trained as architects and work as ȘEZI (Sit) in Hăpria, Alba county. For their sculptural wooden furniture and accessories, they draw inspiration from Romanian heritage and reinterpret traditional symbols. For example, a detail of an antique chair may inspire them to enlarge it and turn it into a wall sculpture.

At the Hotel Conacul Olarilor in Baia de Fier, they have been able to put many of their ideas into practice, as the owner Mihai Olaru himself, is also a devotee of Romanian customs, and tries to revive it in a creative, contemporary way.

which is modelled on a detail (above) of the antique chair

Hungarians in Romania

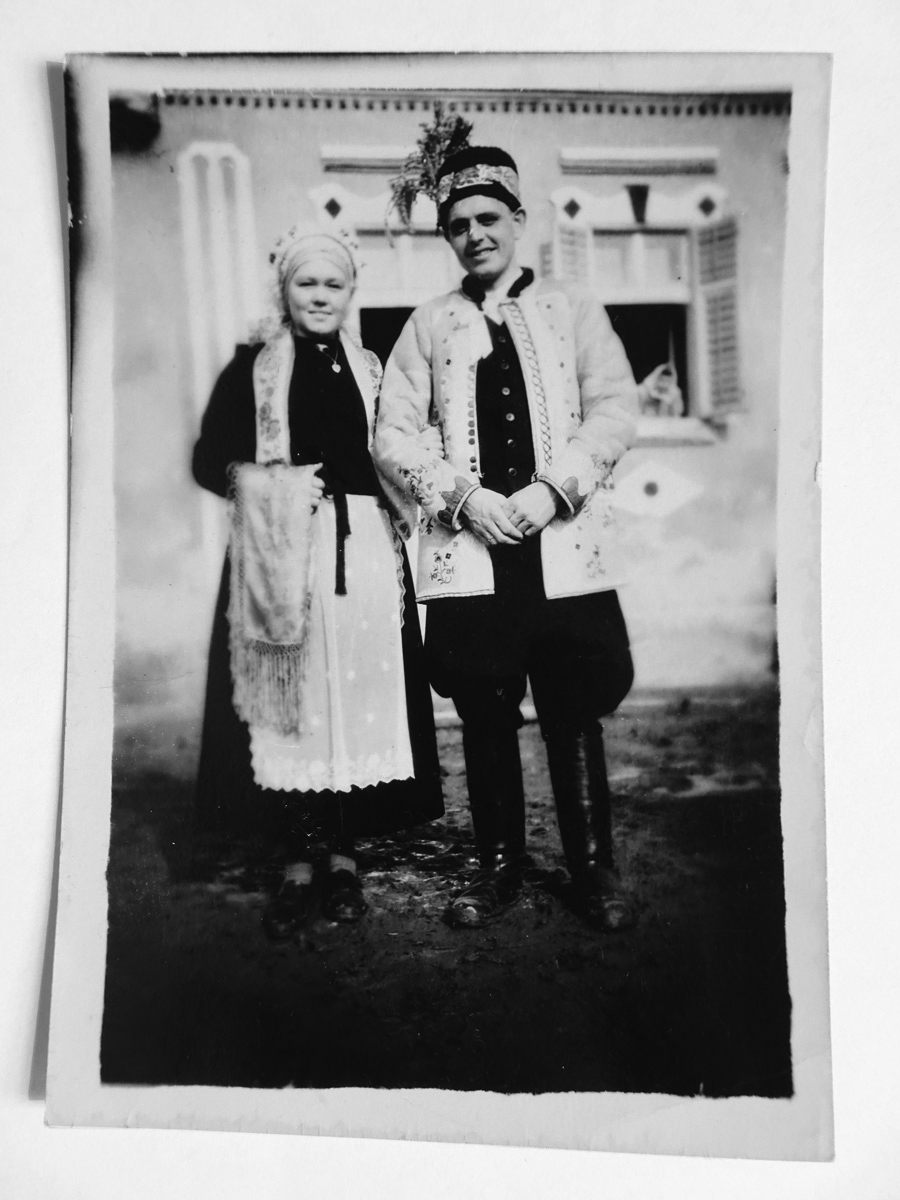

Viştea, Transylvania (RO), year unknown

The Hungarians are the largest ethnic minority in the country. The Szekler form the largest group among the Hungarians in Romania.

Between the 13th century and 1867, the Szekler acted as frontier guards of the Hungarian kingdom and enjoyed important privileges. They had autonomy in many areas of life and were able to emphasise their own identity. Today, the centuries-old cultural heritage of the Hungarians is visible in folk costumes and traditions.

Viștea, Transylvania (RO), 1931

Iren Orbán was born in a village in Székely Land, Romania and although she is over 90 years old, she still embroiders for her family. Her stitched narratives of village life are a visual documentation of Hungarian traditions.

Kath Griffiths, a collector and dealer, became passionate about Hungarian folklore 20 years ago and started her collection Parna (Hungarian for cushion). She is currently documenting the last ‘dowry rooms’ in the Calata region (Kalotaszeg) in Western Transylvania. In these rooms the bride’s trousseau used to be presented. It included self-woven textiles, self-tailored costumes, painted ceramics and chests, embroidered cloths and cushions. Kath Griffiths also offers Folk Tours to get a first-hand impression of the Hungarian influences in Transylvania.

documented by Kath Griffiths

In 2019 the parish Church in Bákó (Bacău, Transylvania) was filled up with Csángó people after the Roman Catholic diocese Jászvásár allowed to hold a Hungarian-speaking mass after almost 30 years. Since the change of the communist system, this Hungarian ethnic group, was only allowed to go to Romanian masses. The equality of ethnic minorities in Romania is not yet a self-evident fact in daily life.

Harghita County (RO), 1885

Romani in Romania

Europe, 1930s

The Romani people (colloquially known as Roma) are the largest ethnic minority in Europe, and, after Hungarians, the second-largest in Romania. Linguistic evidence has shown that their roots lie in India an that they arrived in the Balkans in the 13th century. In Romania the institution of Romani slavery existed, especially in fiefdoms, for centuries.

The life of the Roma was mostly documented by foreign travelers. Even today, their history is hardly mentioned in official history books.

Actress and director Alina Șerban, born into a Roma family, addresses in her projects the long-silenced history of the Roma in Romania. With Bilet de iertare (Letter of Forgiveness, 2020) she produced a short film about the slave trade with Roma in the 19th century.

In her autobiographical play The best child in the world (Das beste Kind der Welt, 2022) Șerban wears a ‘crow’ mask as an allusion to this derogatory word for ‘Roma’. Documentary photographer Bogdan Dincă captured this in a fascinating photo series. With her own Untold Stories Artistic Company, Alina Șerban tells unknown and inconvenient stories about Roma to denounce their discrimination, with the aim of leaving it behind.

by Alina Șerban, National Theater Bucharest, 2022

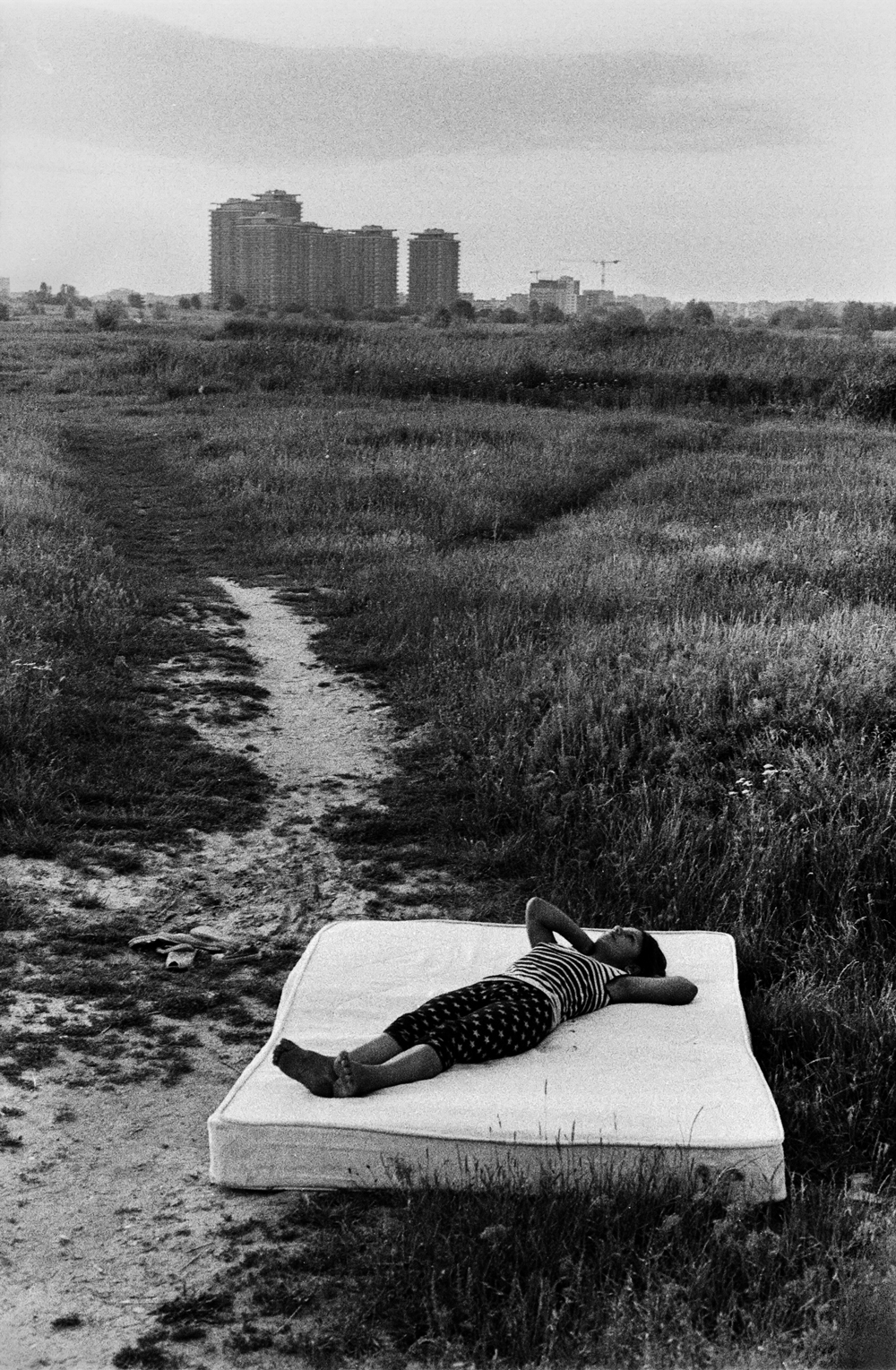

Bucharest photographer Dragoş-Radu Dumitrescu documented the life of a Roma family near the North Station for seven years.

After accidentally discovering their shelter in 2013, he was invited back several times until they were evicted in 2020. Dumitrescu delves into their lifeworld – once nomadic, the Roma are forced to adapt to urban mechanisms in order to make a living. Despite everything, they have retained their passion for their traditions. Dumitrescu shows their fragile everyday life in an impressive long-term documentation.

by Dragoş-Radu Dumitrescu, 2013-2020

Dragoş-Radu Dumitrescu is fascinated by the boundless sense of freedom that some Roma cherish. He also met a Roma family living in the Văcăreşti district on the outskirts of Bucharest, a marshy area that was created in the late 1980s. It is an ecosystem with fauna and flora similar to that of a delta. The family has lived here for more than 15 years, penniless, in self-built shacks, but in harmony with nature. They prefer isolation to the pace of city life.

Dumitrescu captures the harshness and exceptionality of this existence in untouched nature in enigmatic black and white images.

His documentary comes to a forced end when the Romanian government decides in 2016 to grant the Văcăreşti site the status of a protected natural area and the homeless living there are gradually forcibly relocated.

by Dragoş-Radu Dumitrescu, 2013-2020

Transylvanian Saxons in Romania

Lechnitz, Transylvania (RO), ca. 1935

The Transylvanian Saxons crossed Europe in the 12th century and moved from the Middle Rhine to Transylvania (today Romania), where they built up an extensive cultural heritage over the past 800 years. An exodus of this ethnic minority to Western Europe occurred in the 1990s and most of their material cultural heritage remained behind in Romania.

In their studio KraftMade, Marlene and Alex Herberth transfer ancient wisdom and techniques into impressive, performative objects. Both have Transylvanian-Saxon roots and integrate this cultural heritage into their projects in manifold ways. KraftMade works in an interdisciplinary way, combining design, knowledge transfer, restoration and curatorial activities.

and his Common Table in the exhibition Impatiens Tremens,

curated by Marlene Herberth and Elena Viziteu Ionescu,

Romanian Creative Week, 2023

The Transylvanian-Saxon textile artist Lilian Theil from Sighișoara (RO) processes autobiographical and historical themes in her ‘rag pictures’. Among other issues, she depicts the deportation of Transylvanian Saxons to forced labour in the Soviet Union in 1945 or their exodus in the 1990s. Curator Raluca Ilaria Demetrescu compiled a magnificent exhibition of the artist’s work in 2021.

Art Safari Bucharest (RO), 2022

Katharina Wagner-Birtwistle’s father was a Transylvanian Saxon who remained in Britain after being a war prisoner during the Second World War. As a child, Katharina spent her summer holidays in Apold, Transylvania, playing in meadows and making soap with her grandma. In 2018, these experiences inspire her to start her company Apoldapothecary, where she makes natural soaps with scents reminiscent of Transylvania.

is standing in the back, to the right of her husband Michael

Apold, Transylvania (RO), 1928

the method also used by her grandmother in Transylvania.

Jews in Romania

Iași (RO), 1918

Their history is marked by ups and downs in terms of their political rights. Formally, the Jewish community received constitutional equality in the Principality of Romania in 1859. In 1876, even the first Yiddish theatre in Europe was founded in Iași. After that, the rights of the Jews were increasingly curtailed. During World War II, some 350,000 Jews were killed in collaboration with the Nazi regime. A public reappraisal of Romanian participation in the Holocaust is still in progress.

Veronica returned after the Holocaust

as one of the few Jewish girls from her school.

The only one of 28 synagogues in Galați

to have survived the course of history.

The Jewish Historical Museum Muzeon in Cluj-Napoca provides an important contribution to the memory of the Jewish community in the city and in the country. Drawing on the archives of the Jewish Lusztig family, a fascinating exhibition narrates personal stories. The founder of the museum Flavia Craioveanu has developed an immersive experience with the help of a highly professional team. Contributing to this are the technical finesse of Dan Craioveanu, the elegant graphics of Cătălina Nistor, the emblematic exhibition design of Atelier MASS and the first-class photographs of Lieven Gouwy.

Cluj-Napoca (RO), 2019-2020

The Maramureș Heritage Association commemorates the Jews of Baia Mare and its surroundings through cultural projects. The initiator, Robert Cotos, is a passionate storyteller who feels it is essential to educate the locals about this forgotten history.

Satu Mare, Maramureș (RO), 1929

Turks in Romania

Their history began in the mid-16th century when the Ottoman Empire gained control over what is now Romania, including the principalities of Moldavia, Wallachia, Transylvania and Banat. To this day, there is a Turkish minority in Romania, living mainly in the Dobruja region near the Black Sea in Constanța and Tulcea counties.

Dobruja (RO), 1930s

Dobruja (RO), 1930s

One of the most important Turkish cultural monuments in Romania is the Carol I. Mosque in Constanța. It was built by Romanian King Carol I as a tribute to the large Muslim community in the city at the time and was personally consecrated by him in 1913.

of the Carol I. Mosque, Constanța (RO), 1913

Constanța (RO), 2019

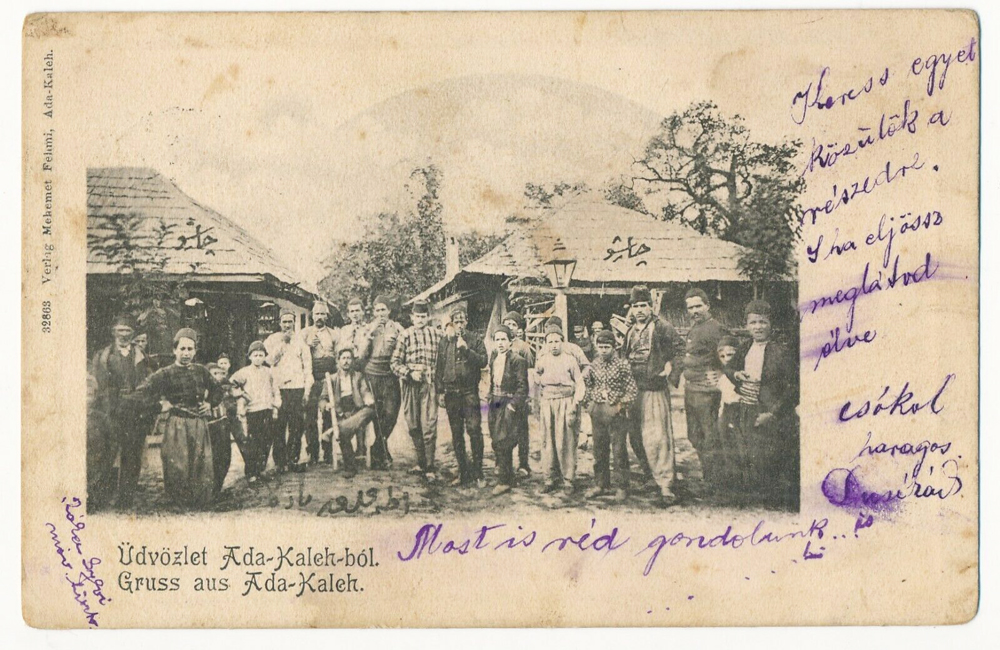

Souvenir photos from Ada-Kaleh, an inland island in the Danube whose Turkish inhabitants were forcibly resettled from 1968 onwards because of the construction of a Romanian-Yugoslavian power plant. Later, the island and all its villages were flooded by the backwater of the power plant.

The Turkish Democratic Union of Romania is the only organisation recognised by the Romanian government that is led by ethnic Turks who are Romanian citizens. Its main objective is to protect and promote the ethno-cultural, linguistic and religious identity of the Turkish minorities in the country. Thus, as in Turkey, Youth and Sports Day is celebrated in a major way in memory of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk on 15 May.

during the Youth and Sports Day, Constanța (RO), 2023

Documentary photographer Florin Ghebosu makes an impressive coverage of the Turkish community in Dobruja (2017-present). Among other places, he takes photos in the municipality of Dobromir, where the majority population is Muslim. His photos provide insights into a destitute but colourful everyday life.

Before he started photographing the villagers, he told them about his work by showing them his reportages. This honest approach is the basis on which Ghebosu manages to make unvarnished, often intimate portraits. In the meantime, he knows some families there so well that he returns regularly and his project has developed into a long-term documentary.

by Florin Ghebosu, 2017-present

In this article I present a limited, personal selection of people and organisations involved in the preservation of the cultural heritage of Romania. The minorities I have not mentioned also contribute significantly to the revival of this tangible and intangible heritage.

In the past, the various ethnic groups cultivated their culture in great isolation from each other. Fortunately, interest in each other has increased in recent decades. This interaction not only leads to sustainable, social interactions, but also promotes a more truthful approach to Romanian history. This is the only way to recognise the true value of this complex cultural heritage. Its preservation is undoubtedly a joint effort.

Follow my visual research on Instagram.

Share: