A visual short story by Gerlinde Schuller

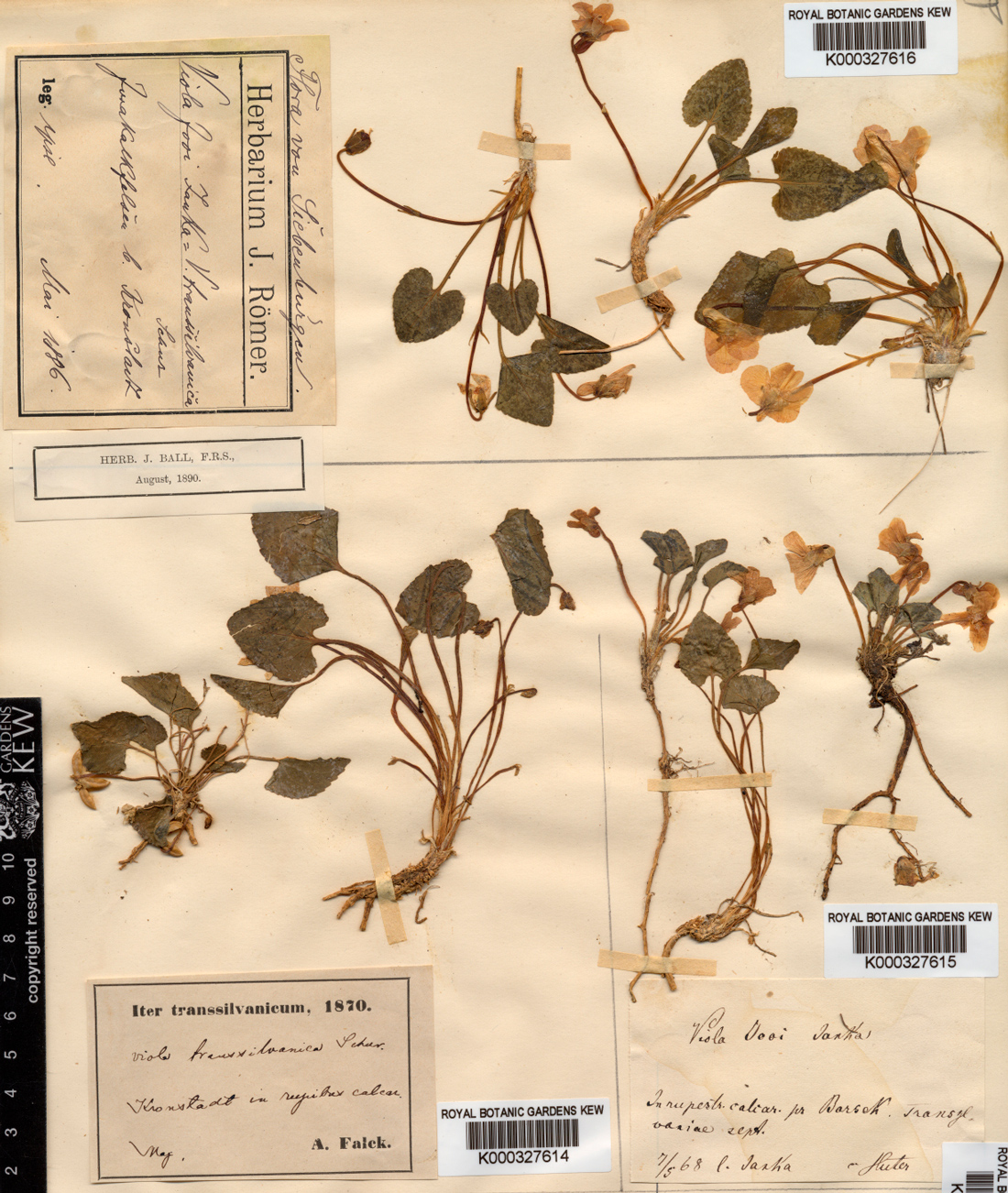

Transylvania, Romania

In Mediasch, which some call Medgyes, others Mediaș, people went about their daily routines on this morning.

For Elfriede Binder, called Friede, it is not a usual day. She was supposed to go weeding in the fields, clad in working clothes and an old straw hat.

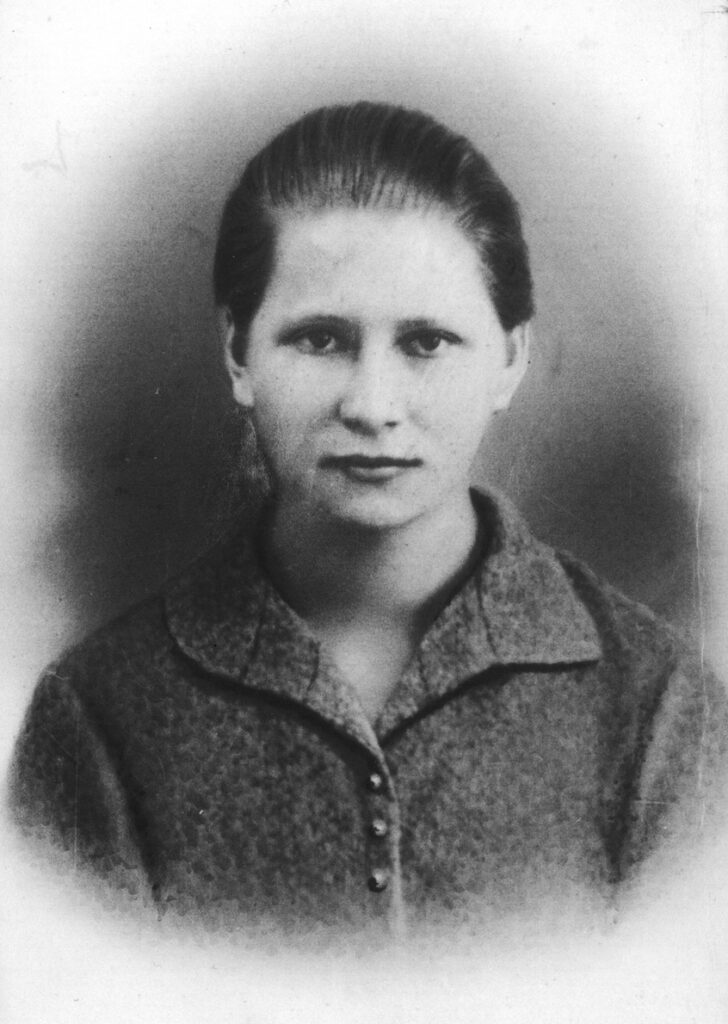

Instead, she enters the prestigious ‘Photographic Studio Alfred Adler’ in a self-made dress of fine wool to have her picture taken. She cannot know that her urge to memorialize herself will trigger a chain of events that even a hundred years later will take its toll.

Her thoughts revolve around the money for which she stinted herself, and the five other hungry mouths, to have her picture taken.

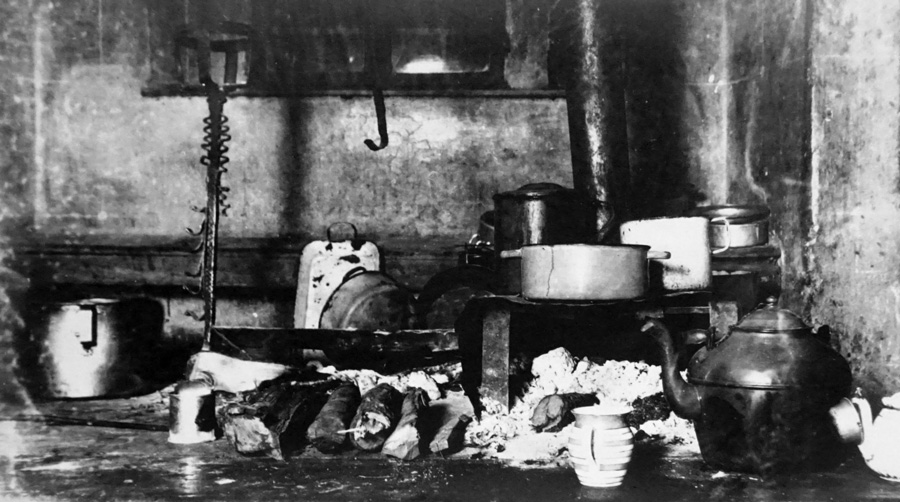

For months, she used less bacon for the Hanklich and less meat for the Tocană, and turned the remaining foodstuffs to hard cash at the market.

The time has finally arrived. Friede is sitting in the photo studio in front of a painted wallpaper depicting a faded landscape.

Stiff with tension, she shifts back and forth on the wooden stool, pushes her long braids back and repeatedly strokes her hair.

While her heart is in her throat and a pleasant warmth crawls up her cheeks, she leans her head against a wooden support standing invisibly behind her.

Ever since Friede squeezed herself into the tight velvet camisole of her garb and donned the stiff braid for her wedding photo, she has wished for a portrait.

Just of herself. In a Sunday dress and without headgear. If her mother were still alive, she would have put this down as a waste of money and forbidden her to do it.

Friede hasn’t been able to recall her mother’s facial features for a long time. A family photo once existed, but it is mysteriously missing. The only thing she inherited from her mother was her forename Elfriede.

“Sit still, Mrs Binder. I’m ready.”

The photographer disappears behind a black velvet cloth attached to a monstrous camera.

“Look straight ahead, right into the lens.”

Friede smiles with her mouth shut. She has been eagerly awaiting this moment for years – three, four seconds, all alone, at the absolute centre of attention. She doesn’t suspect that this will have to suffice for her entire life, that it is her first and will be her last portrait.

“And… done.”

For Mr. Roth, the Transylvanian-Saxon photographer on duty, the simple photo is a routine task. More and more farmer’s families can afford coming to the photographer, and he is earning well.

His only worries are about his progeny. His eldest son went to war enthusiastically and has been missing since 1916.

His youngest son fled to America to escape the war and is now fighting the flu. Not that this invisible enemy spared Transylvania, but after the Romanian Queen Marie survived the disease, the Romanians felt immortal. They hung garlic pearls around their necks and celebrated the new Greater Romania, only to go to war again a short time later.

The world is upside down. But Mr. Roth is not yet ready to give up his paternal rule and bequeath his daughter. For now, he has cast a veil of silence over the unpleasant affairs and waits for his sons to return.

”We’re done, Mrs Binder. You can pick up the picture next week. Simple wooden frame?”

*

As soon as Friede fetched the black-and-white photograph, she tasks her oldest daughter Elfriede with hanging it over the divan in the farmhouse parlour.

“Mother, it looks as if you were dreaming with your eyes open.”

Elfriede skilfully hammers the nail into the wall and hangs the picture evenly at the first try.

“When will a photograph of me be taken?”

Her mother briefly looks up from her cross-stitching. “Don’t talk so much.”

Elfriede bites her tongue, collects the tools, tiptoes to the courtyard and, like every evening, tends to the chickens, the pigs and piglets, the cows, the horse and the dog. Mother has given them too little to feed on in the past months.

Everyone has had less to eat. There was no meat on Saturdays, and she pacified father with muscatel wine. And all that just so mother could hang up a portrait of herself that Elfriede looks at reproachfully. While cooking, while eating and shortly before bedtime, when she mulls why mother hasn’t been speaking to her for days.

Friede talks all the more with relatives and neighbours. She insists on telling everyone about her exciting visit to the photographer and discretely pushes them towards the bust portrait.

The visitors suddenly find themselves surrounded by two Friedes. One observing them from the side, waiting to see how they react. The other looking them straight in the eye, and no one can elude this gaze.

It is as if one were looking at Friede through a telescope. She stands in a round scenario with blurred edges, as if caught in a crystal ball.

*

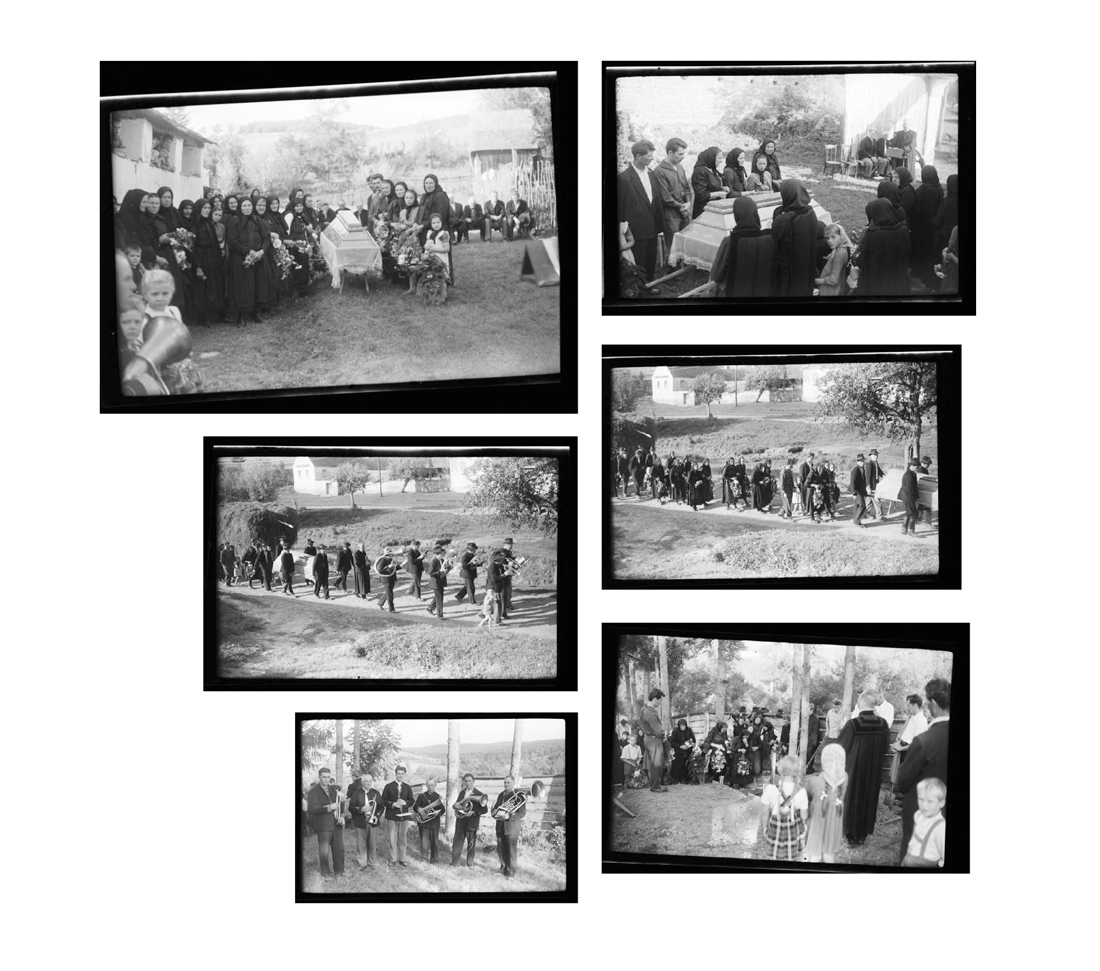

A few years later, Friede dies after a difficult childbirth. Her very last look is at herself. Facing the frame, she falls asleep. In her place, the picture continues to take part in what goes on at home. It is as if it were listening and watching, only Elfriede has the feeling that it sometimes breathes as well.

Elfriede takes charge of the household at the age of eleven, caring for the father and the four siblings. When her mother’s picture is taken down a year later at the father’s behest, she hides it behind the kitchen cupboard.

The picture hears the stepmother and her two daughters moving in and taking control.

It hears fights, punishments and weeping, and notices how fear comes and goes, at some point to nest forever.

*

Soon deafening storms of applause and oppressive silence alternate tirelessly and not only Elfriede loses the overview.

People shed their skins. Today in the form of a friend, tomorrow in the form of the enemy, they voluntarily go to an eternal war.

With the Red Army, only apparent peace comes to the village. Those spared by the war are deported to Russia and subjected to forced labour. Those who can hide in the vineyards and evade deportation, must witness their expropriation.

A first ray of hope is Fred, a smart guy, asking her father for Elfriede’s hand in marriage.

Without looking back she leaves the farm that has belonged to the family for countless generations.

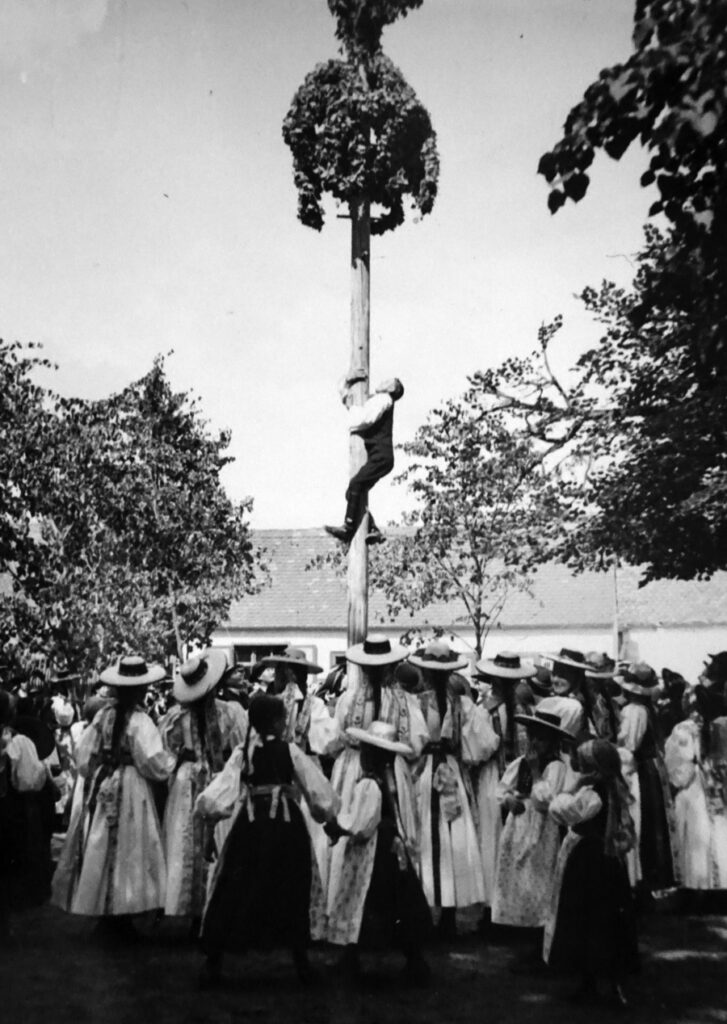

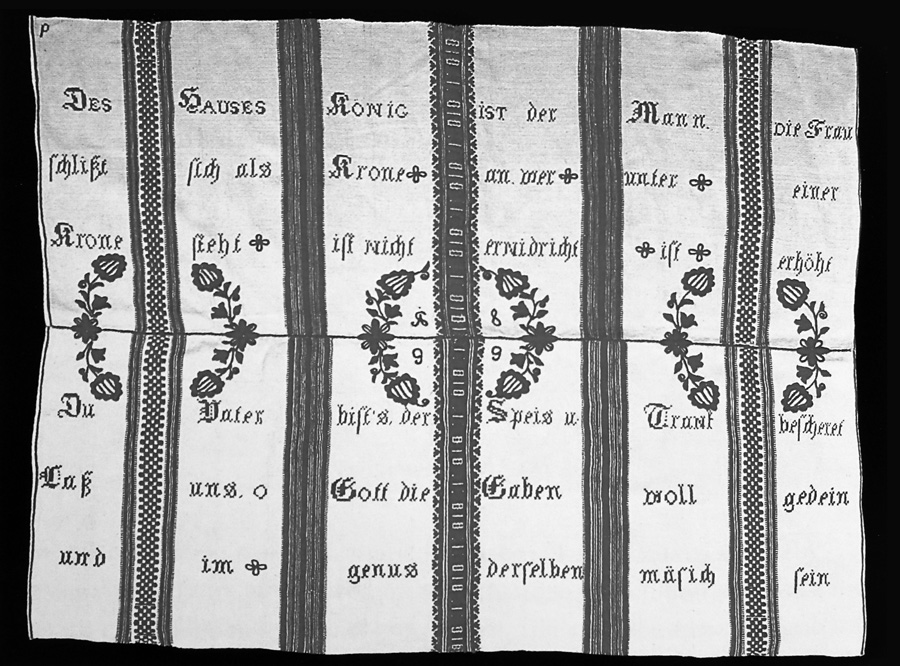

Whoever stands under this crown is not degraded but elevated.

Her father insists that, along with her dowry of self-woven tablecloths and a wooden table, she also take the picture of her mother, since this valuable memento is due to the eldest. And so the portrait of Friede is brought into the light of day again and wanders to the other end of the village.

To honour the mother-in-law unknown to him, Fred even suggests hanging it on the veranda, for all to see. For the sake of peace and quiet, Elfriede agrees. Only the priest and the own parents are worthy of reverent worship, which may not be denied.

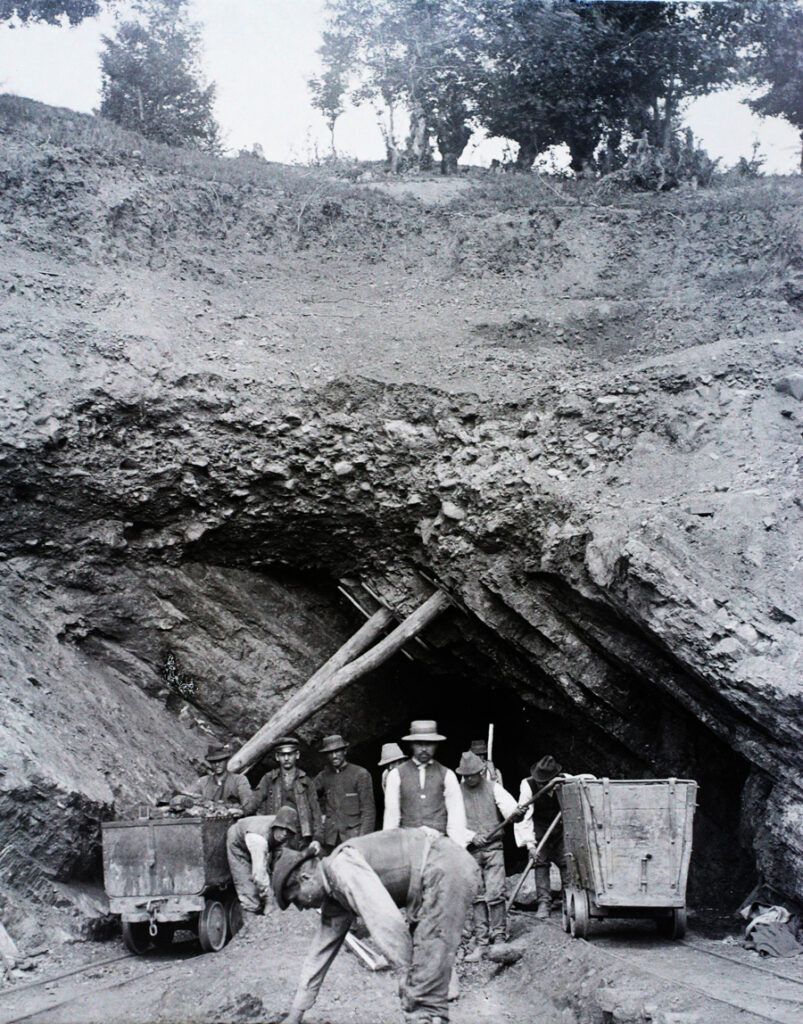

Fred cannot avoid being drafted to the military. He is ordered to work in the mine, where the soldiers are told to make Lupeni the most important hard coal supplier of Romania.

The Communists have ambitious aims that others must achieve.

When his daughter is born, Fred is far from the village, in a shaft deep down in the rocks of the Carpathians.

In his absence, the girl is baptised Elfriede. The custom of giving the oldest daughter the mother’s forename is not negotiable. The picture on the veranda consents to this matter of course. The sense of obligation is fulfilled, and from now on everybody in the village calls the child simply ‘Elli’.

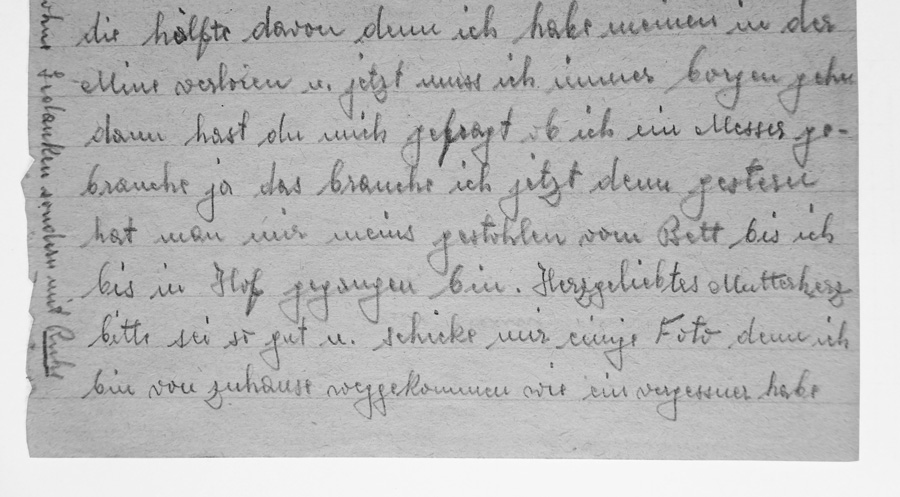

In his last letter, Fred asks for razor blades and photos, but before he can see his daughter, a coal pit collapses and buries him.

After Fred’s death, Elfriede ossifies to a still image. She veils herself in black and in silence. Someone must be to blame, and Elli is the appropriate scapegoat. She can’t anticipate quickly enough what must be done and is always at the wrong place at the wrong time. Elli can no longer make her mother talk, she just makes her furious. She is good at hiding her black and blue marks and spots of torn-out hair. Over time, she mimics her mothers silence and learns how to ably duck down.

This silent humility comes in useful for the Romanians, who seek to get the Transylvanian-Saxons back for what they themselves suffered in the last centuries.

Elli has the best grades, but a German name. What is more, she is a female and from a village. A devastating combination that has no place in the gymnasium of the big city.

History does a backwards somersault and repeats itself in never-ending unison.

*

Sam, a young chap from the Obergasse, casts an eye at Elli at the Crown Festival.

They both grew up without a father, something that forms a bond. Sam’s father stayed in Germany after the war, and Elli knows her father only from photos.

At their wedding, she wears her mother’s garb and in the old tradition sings: “Farewell dear parents, with joy I thank you for all the good you have done in my youth.” She recites verse after verse, and the lies never end, but rituals are vital, so she keeps on singing.

Sam and Elli buy a little house below the forest. Elfriede also moves in and with her the picture of Friede. Elfriede keeps watch of the household, Friede of propriety and morality. She again hangs in the parlour at the centre of events and turns up her nose when Elli has a daughter. All would have preferred a son.

The first thing Elli pushes through at home is to name her daughter Anja. The second is to submit an application to emigrate to West Germany.

‘Renegade’, is what Elfriede accuses her of being and refuses to call her granddaughter by her name.

‘Defector’, is what the neighbours call her behind her back, while secretly filling out emigration applications themselves.

‘Hitlerişti’, is what the Romanians call her, leaning back and keeping their cards close to their chest.

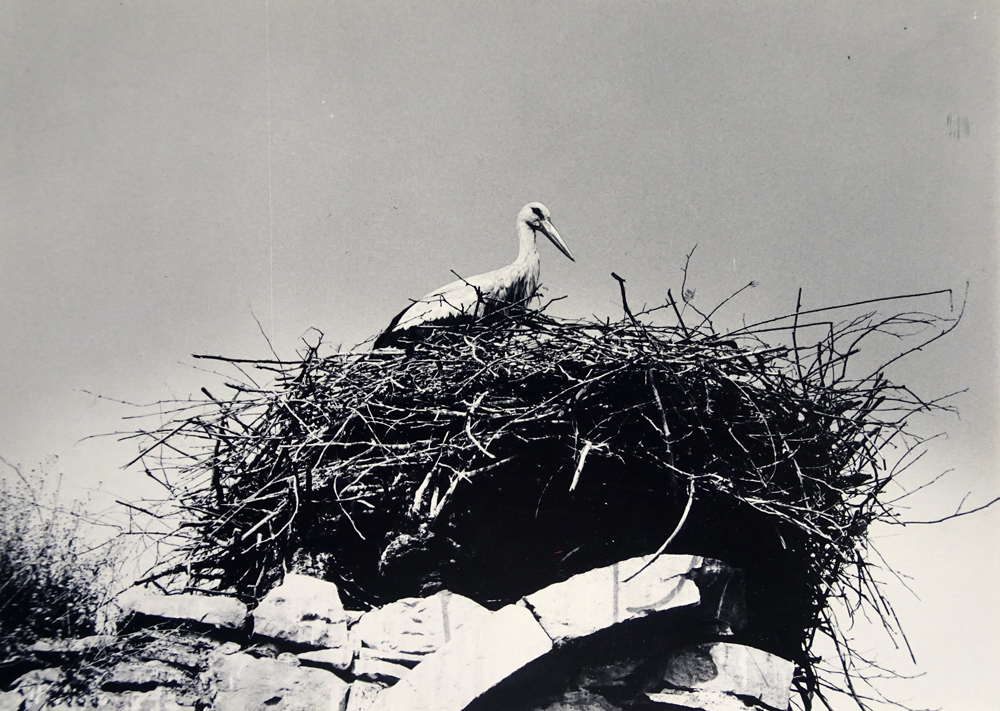

Waiting feels like torture. Elli looks to the heavens and waits for a miracle.

Ever since she saw the pictures of men

on the moon, she is convinced that miracles exist. She wants to make a cloudless future possible for her daughter. And waits.

Meanwhile, Anja and a bunch of kids run after the polished cars of relatives from Germany, when they arrive in the village honking their horns in the summers.

Their stories are filled to the brim with paradisiacal conditions and the boot with coffee, chocolate, second-hand clothes and cigarettes. Not just any brand – it has to be KENT to make time go by faster.

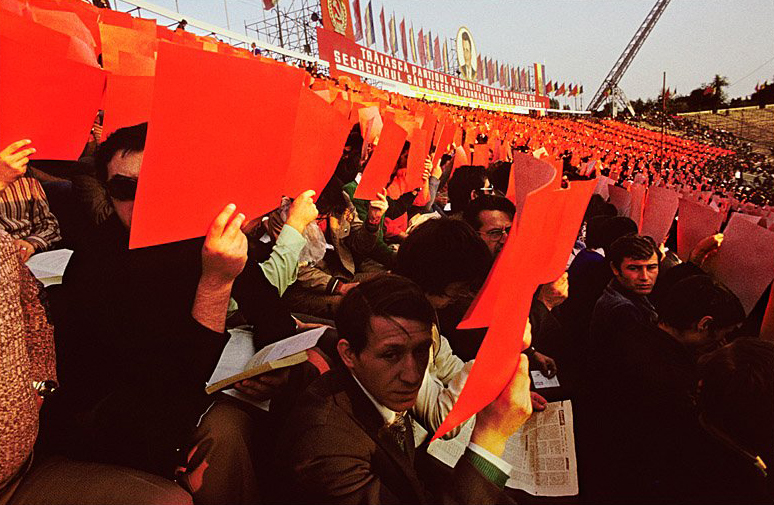

But time won’t let itself be told how fast it should pass. It has a mind of its own and is presently planning big things. The streets are lined for the titan of titans, nicknamed Ceau. Waving flags until one is exhausted and crying ‘Hurrah’ until one’s voice gets hoarse.

A grandiose theatre with just one lead actor and millions of applauders. The spectators are used to watching their own lives impassively. Furious on the inside, silent on the outside. They merge with the anonymous crowd, erasing themselves.

Elli must witness how truth falls apart. What is adorable for some entails harassment for others, and for others yet even death.

She wants to prevent Anja from having to wear a pioneer uniform and eat humble pie in front of a statesman’s portraiture that is excessively reproduced and floods the country.

Time goes by and despair creeps into Elli’s waiting. Since recently, she has been waiting for hours for the next bread delivery at the supermarket. She stands in a queue for flour, butter and oil, and Sam waits what seems like forever in a line of cars in front of the petrol station hoping to fill his tank.

In the meantime, they are channelled through an inscrutable sequence of bureaucratic requirements.

Having documents authenticated, waiting, picking up stamps, waiting, discussing with officials, waiting, initiating administrative procedures, waiting, bribing, waiting, filling in little forms, waiting, filling in big forms, waiting. Until they are finally told to pick up their emigration documents.

Elli has her father’s grave sealed with a concrete lid. As a precaution, she does the same to her heart. Without mourning anything of the past, they start selling and making gifts. Their possessions dwindle. They have to fit in four wooden boxes measuring 120x50x50 cm each.

Finally, the yellowed photo of Friede is taken from the frame and inserted between two pasta boards. Amidst embroidered aprons, towels, carpets and enamelled kitchen-ware, she leaves house and home, the village, Transylvania, Romania.

They have escaped and are returning to where their ancestors emigrated from nine hundred years ago. Basically, they are repatriates.

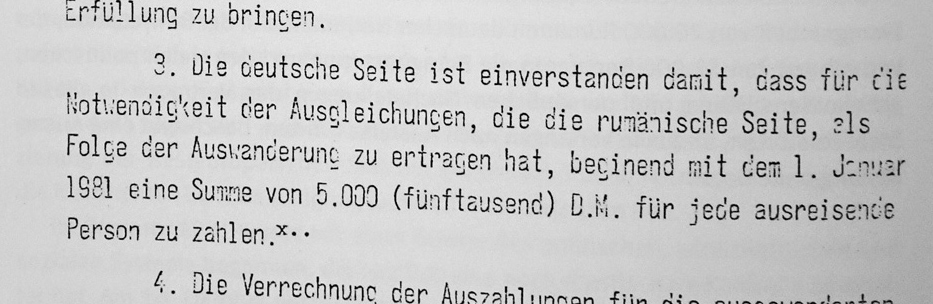

Except after arriving in Germany, that’s not how it feels. Shame crops up as the Germans had to pay a ransom of thousands of Deutschmarks for them.

At night, Anja sleeps with one eye open. She remains alert. New thinking, new customs. The language is the same but foreign nonetheless. Arriving takes time. To make it go faster, the dialect is shed and the accent is ground off.

Elli and Sam forget their common language completely. She lectures on the future. He prattles about the past and only feels happy when he smells horses. Something that is rarely the case in the city, in the middle of a housing estate.

Elfriede never arrives. She mourns her old homeland and the good old days. Elli asks, what good old days she actually means.

Taciturnity increases. And Anja is busy bridging the gaps, mending fences, glossing over deficiencies and settling disputes. When all this is to no avail, she revives the shattered dreams of her parents, of her grandmother and great-grandmother, meticulously threading them and seeking to make them come true, one after the other. She owes it to them to make something out of her life.

Guilt results in duty. The duty to listen,

to mediate, to give without taking.

Duty is followed by coercion.

Never be angry, never feel, never talk.

Be silent.

Silence becomes the essence of things.

When Marie is born, Anja loses her breath.

She looks at her daughter and gasps for air.

Vertigo. Mortal fright. Absolute silence.

Silence is poison. It seeps into the body.

Nerve poison. It numbs all feelings.

Slap yourself. Stay quite.

Speechlessness.

Anja’s gaze comes to rest on Friede.

And she sees herself. A small cog in

the big generation-to-generation

transmission machine.

ElfriedeElfriedeElfriedeElfriedeAnjaMarie

It whirrs. In an infinite loop.

And gets stuck.

Innumerable layers of stillness.

Properly placed upon each other.

Glued to each other.

Only talking, reliving, can now help.

Exposing, giving voice, questioning.

What do I want to pass on,

and what leave behind?

The fictional short story is based on historical facts and events.

Historical Background

Literature Recommendations

The historical images were compiled from more than ten different archives.

Image Credits and Colophon

You can find a larger selection of my visual research material on Instagram.

Share: